“What is success?” poses the Copt. “It is being able to go to bed each night with your soul at peace.”

― Manuscript Found in Accra

As a grown person, you are rarely ever told that you’re doing a good job. Many times we don’t have a frame of reference for how we’re doing until we’ve screwed something up and gotten yelled at…or fired. Or dumped. Or sued. Or arrested.

As a result, most of us move through life feeling like we might not be doing such a great job. While uncomfortable, this is not entirely unhealthy because it helps to cultivate a growth mindset. If you are cognizant enough to know that you might not be doing so well at whatever it is you are doing, then you are probably aware that this means there is room to grow and get better.

Ironically, the people thinking this way are probably doing just fine. Self-doubt in large quantities can be debilitating, but small doses can be a great tool. In questioning what we are doing, we have a chance to grow.

After I got out of music school, I did my best to make a living as a musician. That lingering bit of self-doubt was fuel that helped keep me sharp and at my best. I wrote music for tiny indie films, did instrumental arrangements for church Christmas programs, played on recording sessions, and took any gig I could get. Many of the best paying jobs were church gigs, especially around Christmas and Easter. I am not religious, and probably an excellent candidate for bursting into flames upon crossing the threshold of any religious building. That being said, the people are always kind, the checks always clear, and there is about a thousand years of badass sacred music written by the rockstars of the classical music world. This is partly why big churches typically end up with killer instrumental and choir directors. They are usually competitive jobs.

One Easter I got a call for a job at a massive Baptist church about 20 miles outside of the city. On Easter Sunday I showed up for a small rehearsal before playing two services. I was the only hired musician- everyone else was from the congregation or community. Immediately it was not good. The instrument parts were in different keys and the director didn’t know the cues for the giant video projector and how our music was supposed to line up. Easter is the Woodstock of church music and this was a mish-mash of cacophony. As a professional, this situation feels like being on a burning ship with no way off. Two services and four hours of this for a congregation of a thousand and no way to fix it made me want to rip my hair out.

Nobody else seemed to notice or care- and ultimately that was ok. Because in the end, voices were raised, offerings were offered, tithes were tithed, and the faithful answered the call. I got paid and went home. The takeaway, besides being able to pay my health insurance, was that, while it’s important to do the best you can, sometimes the best thing you can do is let things be what they are and sleep well at night.

This knife was commissioned by a lady I went to college with for her husband, a former Cavalier Scout in the Army and a new father. I don’t have children but I imagine being a new father, where there are so many things out of your control, can be at odds with the capable nature of a military mindset. The intent of this knife, the Scout, is to put some of that at ease. I tried to capture that duality by marrying those two parts together. The handle was made from an old piece of Black Walnut trim molding- solid, seasoned, and strong. The bolster was made from their child’s blanket, which required a lot more care and work. The blanket contained a bit more uncertainty because I didn’t know how it would turn out till it was finished. Peppered in the blanket was one of the gentleman’s old Boy Scout badges to act as a guardian to that uncertainty.

The Scout starts with a drawing:

Profiled and drilled. The four larger holes reduce weight to improve balance:

Centerline scribed on the blade. This is where the cutting edge will be:

The whole thing gets hardened before grinding. This helps prevent warping:

….and despite our best efforts, warping does occur. Since the blade is still hot from the oil quench we have some time to correct it:

Tempering- this gives the blade flex and bend, while also relieving stress incurred during the quench:

Grinding the bevels:

A full flat grind at 36 grit:

Removing the machine marks:

Satin at 320 grit. This took about three hours of handwork. Now on to the other side…

Electrochemical etching of the makers mark:

A baby blanket. I like the stripes. This will become the bolster.

It wouldn’t be a scout without a Boy Scout Badge. This particular badge shows that the younger scout has demonstrated proficiency with and is allowed to carry a knife:

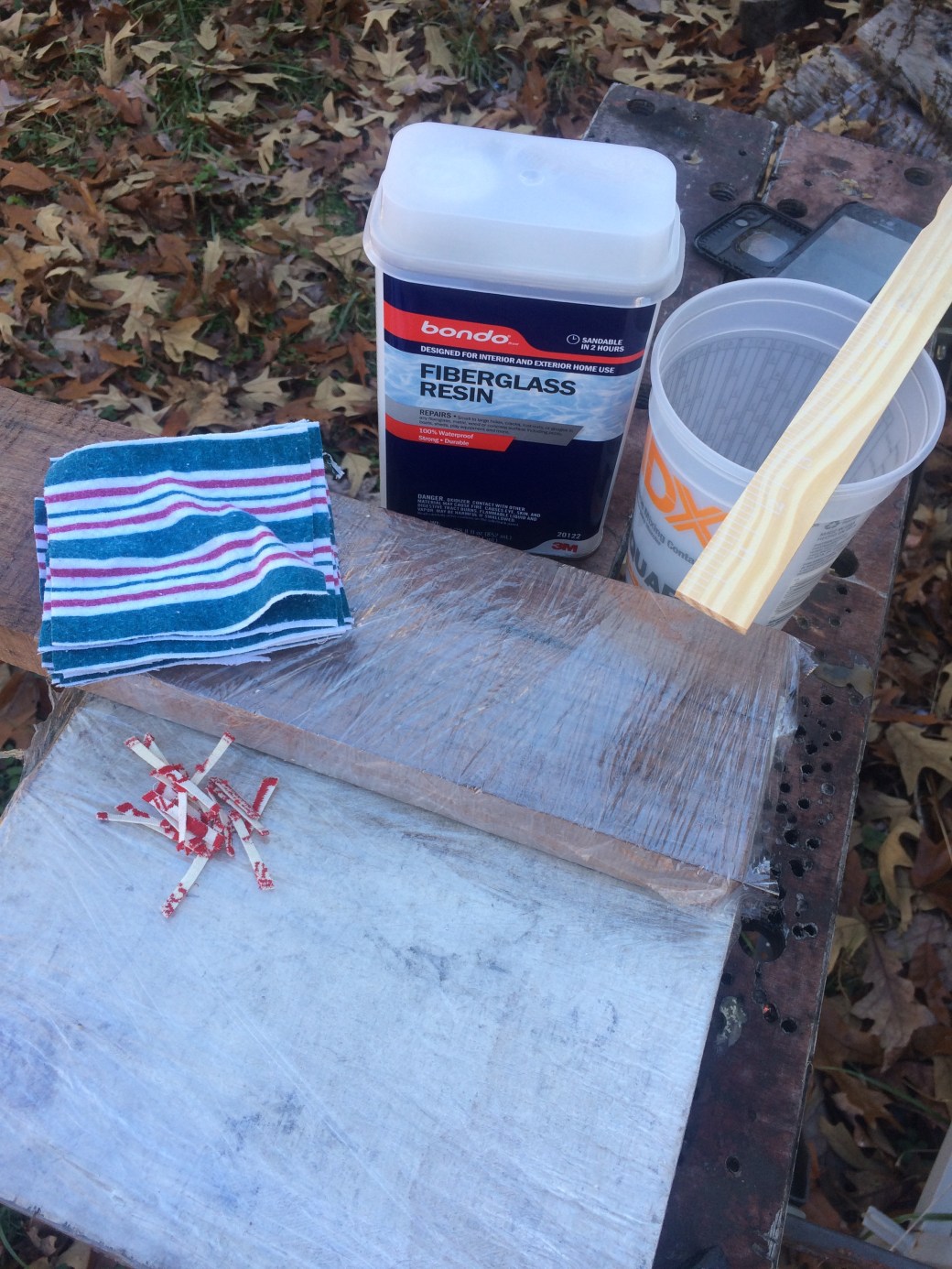

The blanket is cut into equi-sized pieces and the badge into slivers. Everything will be layered with fiberglass resin and smashed together:

After the resin has cured:

A cross-section of the material and you can see the scout badge slivers. This has become one piece of material:

Drilling rivet holes after the bolsters are cut:

This piece of trim molding came from an abandoned house and is made of Black Walnut. It doesn’t look like much right now:

It makes for a better fit if the holes are drilled now before the scales are cut:

Circuit board blank for spacers:

Finally everything fits:

Prepping for glue-up:

Glued and clamped:

Profiling the handle:

Contouring for a comfortable fit. All sanding after this is done by hand:

The Scout: