‘In silence there is eloquence. Stop weaving and see how the pattern improves.’

-Rumi

From mid-January to mid-June of this year everything had been a blur. I was running from job to job, gig to gig, knife to knife, trying to stay on top of everything. Every time that I felt like I had room to breathe, something else would come up. Car repairs, state taxes, doctors’ visits, new tools. It was always something and I was hustling left and right, making sure everything was moving forward and getting taken care of.

Then I had an accident that pretty much stopped everything.

I injured two of my fingers pretty seriously on a table saw. I was cutting some very thin material when the saw bound up and kicked, and I couldn’t get away fast enough. The shop is at my partner James’ house and he happened to be home when this happened. I quickly grabbed a dirty towel and, doing my best not to panic, politely yelled that I needed to go to the ER, right that second.

On the ride to the ER, which was about twenty minutes away, I took stock of the situation. James, who teaches shop and technology education, asked me to double check that my fingers were still attached and not on the floor of the shop. Indeed they were still attached. I would be told later that I was very lucky to keep my fingers- none of the major tendons or arteries were damaged beyond repair.

I do my best to practice calm in my life. Strong reactions happen from time to time, and the best way to deal with them is to feel them, let them pass, and address what caused the strong reaction in the first place. This is an incredibly challenging thing to do and I don’t always do it well but I’ve gotten better at it over the years. On the ride to the ER I found impossible to calm down. I noticed that my thoughts were manic and erratic and I had trouble breathing normally. I felt a pretty deep sense of guilt and shame, as if I had this coming because I wasn’t slowing down. A doctor would later tell me that what I had experienced was an acute stress reaction and was normal for what I had experienced, largely in part from the sheer volume of adrenaline and other chemicals that my body had released.

The ER was a miserable experience. The ER doctor told me they would need to operate but they would need to transport me to another facility because there was no one covered by my insurance at that particular hospital. Nobody even looked at my fingers and I sat on a hospital bed and bled on myself for two hours before someone gave me any pain medicine. The paramedics finally arrived and bandaged my hand- the first time anyone had done anything. They pumped me full of IV fentanyl before loading me onto an ambulance to go to another hospital. Those guys knew how to get shit done, and in my very stoned state I kept telling them how glad I was that they were there.

We got to the next hospital, and my girlfriend met me there. In my state of shock I had forgotten my phone at the shop and James had called her. I was really glad she was there because it would be another four hours before the surgeon showed up. As it turned out he was not covered by my insurance either. Somebody had screwed up.

The worst part about the ER is that you are forced to make life-altering decisions when you are in a state of shock, and/or heavily medicated and not in your best of faculties. The surgeon gave me the option of going ahead with surgery but understood if I didn’t want to- he was very kind and professional, and pretty pissed that this was the way the system was working. I opted not to have surgery that night because it would have medically bankrupted me. I would never have been able to pay that kind of money back. I would have to find another surgeon on my own. He cleaned and temporarily stitched me up enough so that I could safely leave, which involved two incredibly painful nerve block shots and a pretty shoddy cast courtesy of the ER nurse- I think it was her first. By the time we left, my pharmacy had closed and the hospital wouldn’t send me home with any medication. I had to make it the night without pain pills or antibiotics (I would end up taking 2000mg of Keflex a day for 20 days- I was so filthy when I went in they were afraid I was going to give myself sepsis). We went home and tried to get some rest, because the next day would be busy.

I think this was what it looked like when the system fails you.

……

The next morning we got on the phone. We called my insurance company and they found a place that would take a look at me right away. Ironically enough their office was located at the first hospital I had gone to the day before. I met with an orthopedic surgeon and his nurse practitioner.

I found out that orthopedic surgeons do a lot of hip and knee replacements on the elderly, so when a young person comes in with an exciting injury everyone wants to see. I had no less than six people come and look at me, all very excited.

The doctor was really excited to work on me- he was an artist and I was his canvas. He drew me a picture of the procedure he would do and explained the whole thing. They were going to fuse the middle joint of my index finger which the table saw had blown out, and remove a bit of my thumb. I got another two painful shots of nerve block while he examined everything and moved some things back into place. There aren’t a whole lot of words to convey how painful those shots are- I nearly crushed my girlfriend’s hand with my good hand. My surgery would be two days from then, and they told me to rest. So that’s what I did.

I have always had trouble finding quiet places and allowing myself to rest. Now I had no choice. I called my work and told them what happened and that I wasn’t sure when I would be back in. I had to cancel some contractor work and push back a lot of client work. That was what hurt the most. My girlfriend and I watched a lot of Netflix, something we rarely ever do together. I don’t watch a whole lot of TV but over the next week I would watch more TV than I had in the past five years. And honestly it was really nice to check out. I slept a lot and took pain medication and was generally kind of dopey. I told my girlfriend that she was beautiful and I loved her, frequently. I couldn’t bathe myself, or put my contact lenses in, or dress myself. I just had to surrender to everything and let myself be helped.

…..

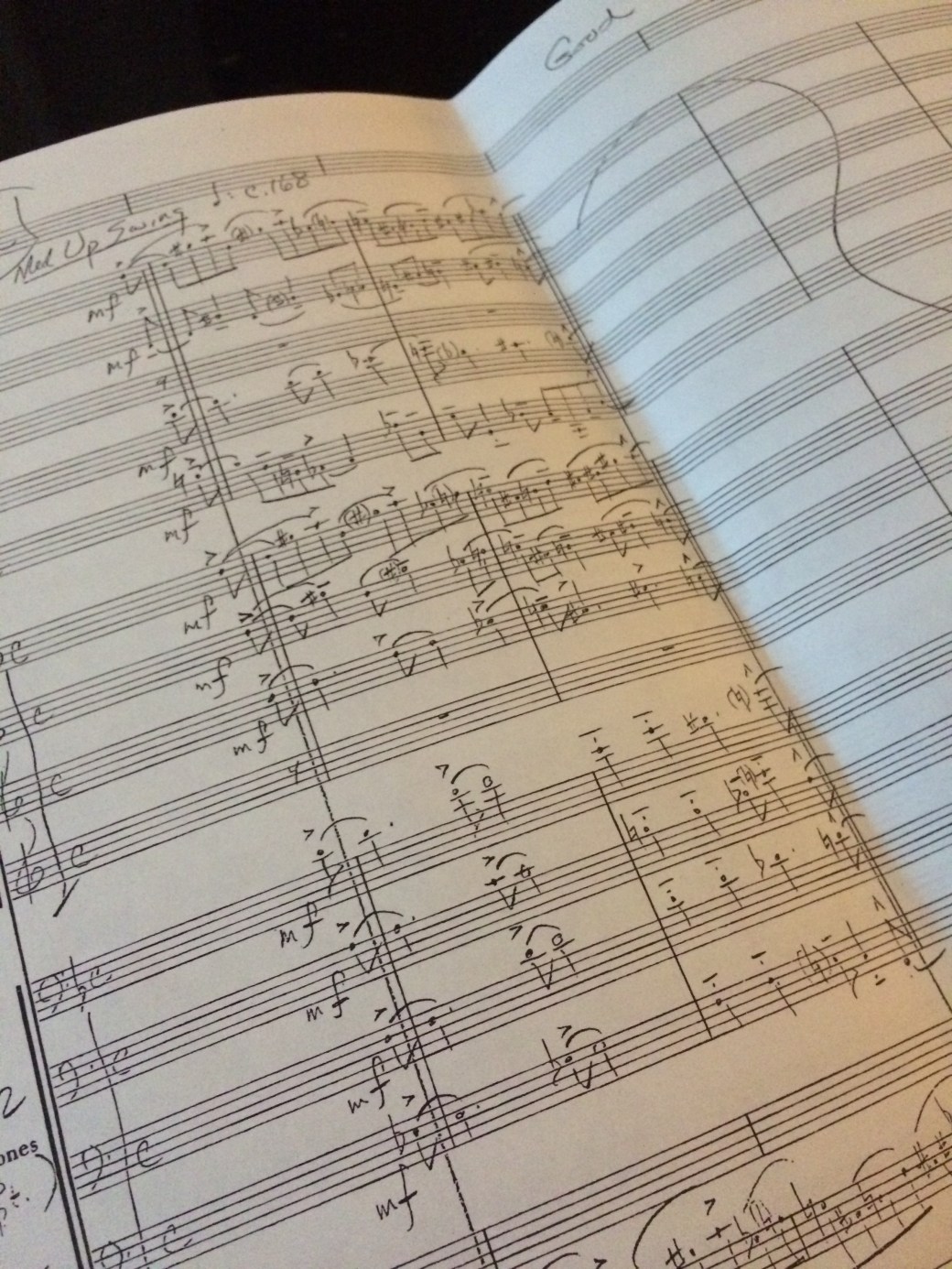

Two days later we went to have surgery done. I have never had any surgical procedure done before and was really nervous. They took me in the back and had me put on a hospital gown and fixed up an IV in me. After a large bump of a sedative they gave me a giant nerve block shot in my shoulder, which made my entire arm go numb. I was dopey but still semi-conscious when they wheeled me into the OR. They had music piped in- Bryan Adams was playing. From what I understand of these things, the anesthesiologist has you count backwards from one hundred till you knock out. Apparently they didn’t do this with me- I knocked out on my own singing ‘Heaven’ from Canada’s most famous musical export. I think this was an auspicious sign.

…..

After surgery everything was kind of fuzzy. We went home and my girlfriend put me in her bed and told me not to get up while she went to pick up my prescriptions. My entire left arm was completely numb from the nerve block and I remember being really hungry. Apparently I got up and ate an entire box of her kids’ Pop-Tarts while she was gone and then swore to her that I didn’t. There were Pop-Tart wrappers all over the place- I don’t remember any of this. I slept a whole lot and my dead arm, which I was supposed to keep elevated, kept falling and hitting me in the head. I had a whole pile of pills that I had to take and my girlfriend dutifully kept me on a tight schedule. The best I could do was tell her that I loved her and tell her how beautiful she was.

The next four days passed like that. She took off from her high stress-job and looked after me. She helped me bathe, made sure I was taking my medicine, and kept me fed. I would get really weepy from time to time. It was all a lot; the trauma from the accident, the bone-deep pain from the surgery, and the bills that would be coming (because even with insurance these procedures are very expensive), and the people I felt I had let down. Then there was this really wonderful woman taking care of me telling me that it was ok and how well I was doing. The pain medication peeled away all of the armor I usually wear to function in the world and so from time to time all of this would hit me and I would just sit there and cry.

A few days later we went to clean up my apartment. I had gotten off the major pain killers to see how my hand was doing so I could get back to my day job. In situations where there is a caregiver and a care receiver things can turn toxic and codependent— I’ve seen it happen. The pain pills can be addictive and I didn’t want to be a patient or lean on anyone if I didn’t have to.

I had a couple of my friends come over to help. I couldn’t really do a whole lot. My girlfriend spent two hours cleaning my shower- a knifemaker’s shower can get really dirty. One of my friends washed all my dishes for me. James had let me keep my car at his place till I could drive again, and I finally went and picked it up. And I started going back to work.

……

My two fingers have been in special splints as they heal, so I’ve been doing everything with eight fingers instead of ten. All the simple things I do that I never think about, like brushing my teeth or packing a backpack or making a sandwich, suddenly require a lot more thought and take twice as long. It’s really draining and frustrating and a full day of that makes me really tired.

One thing that continually catches me off guard is the amount of help that is available. Whenever there is something I can’t do there is always someone right there to help. Shortly after the surgery I was working a large concert and I had trouble getting a pack of snack crackers open. I had to grab a union stagehand, an older gentleman with a long white ponytail, and ask him if he could open my crackers for me. “Well sure brother,” he says. “Everybody needs a little help now and then.” Cue waterworks from me.

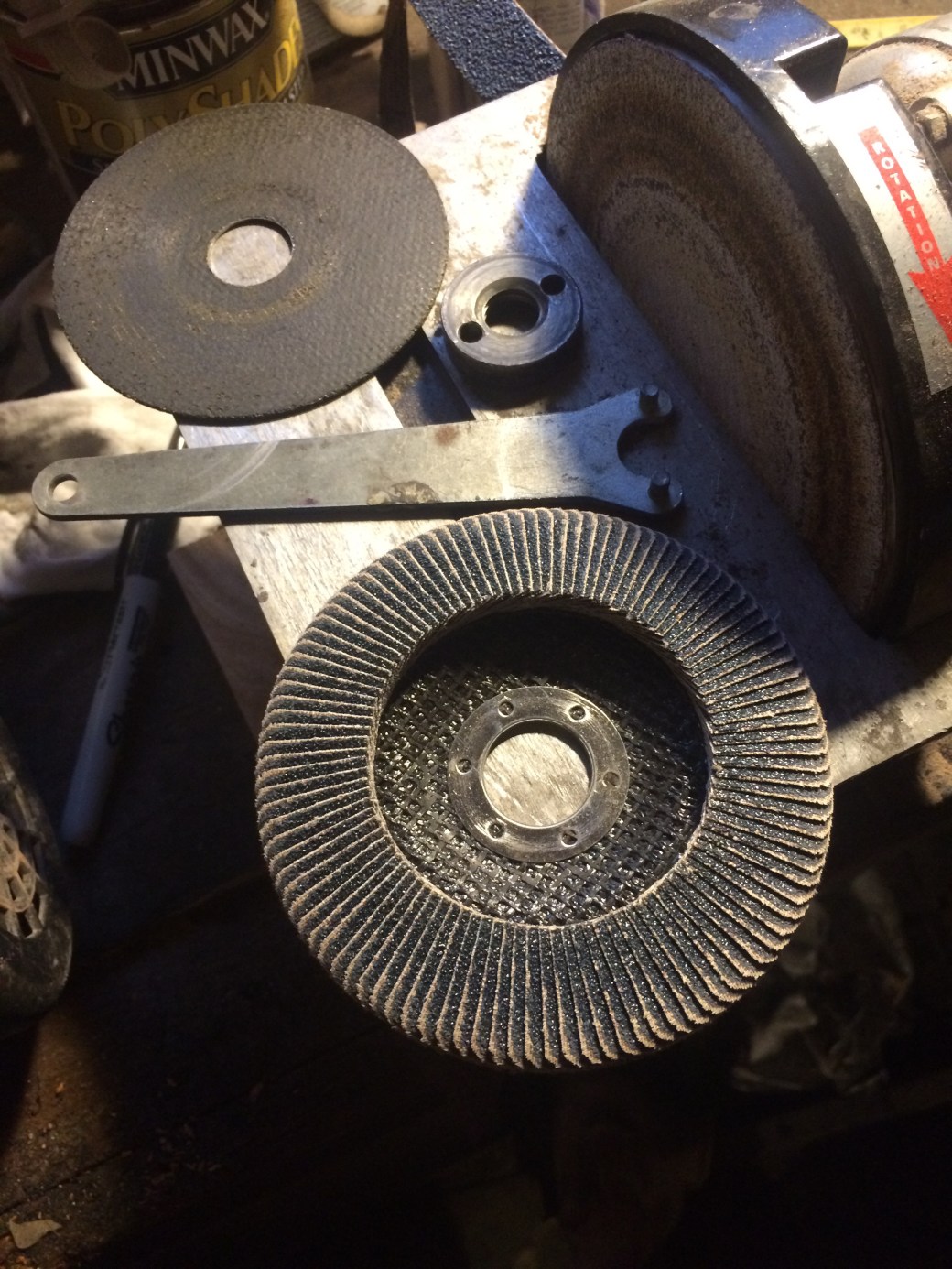

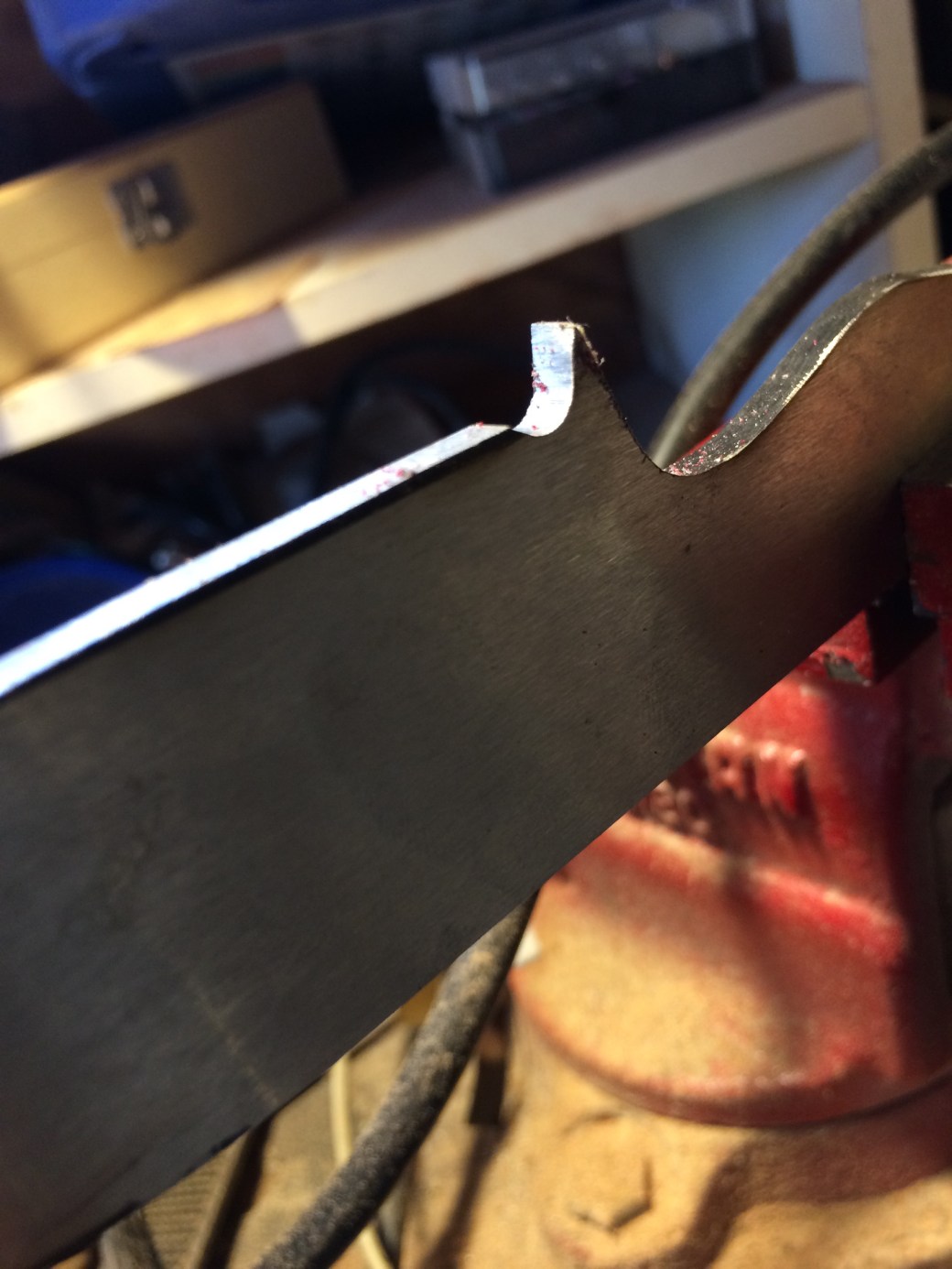

Getting back into the shop has been scary, and a slow process. I was in the middle of this knife when I injured myself and I had to keep emailing the client to push back when I would have it finished. I did all of the woodworking and leatherwork with eight fingers. It’s been an exercise in leaning into fear and getting back on the horse.

I tend to have a lot of quiet days of late. Quiet days allow everything to settle and help one’s focus to reset and help one to cultivate a sense of gratitude. They also allow for deep processing and healing. This is also lesson of the Woodsman. Any good person of the Woods knows how to find quiet and the goodness that comes from within. The second part of this build has been an exercise in just that.

O1 tool steel, out of the forge:

Hand sanding:

Computer board for the spacing material:

Mesquite from Texas for the handle:

All profiled:

Rough shaped on the grinder- from here out it’s all hand work:

This is at 220 grit:

Letting a bit of oil set in to help the grain to speak:

The Woodsman, Mark II:

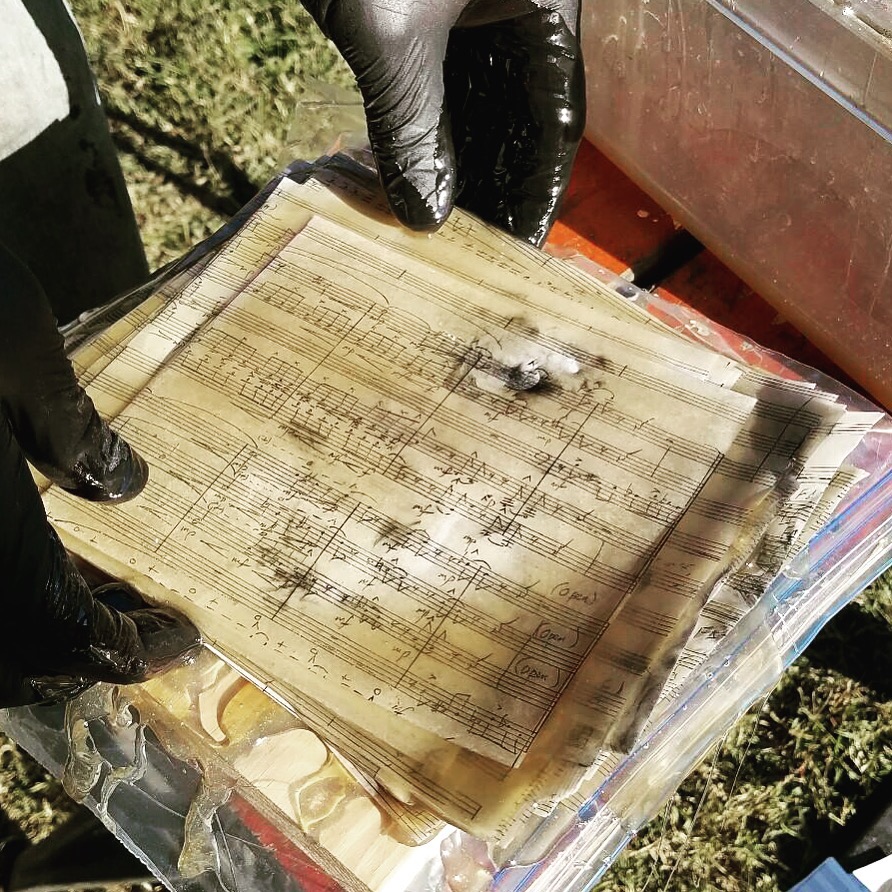

In a continued practice of saying ‘yes’ I chose to use some of the Black Walnut I got from the tree job for the handle material. It fit nicely into the story of these knives. This is what it looks like sanded and polished.

In a continued practice of saying ‘yes’ I chose to use some of the Black Walnut I got from the tree job for the handle material. It fit nicely into the story of these knives. This is what it looks like sanded and polished.