“So many people live within unhappy circumstances and yet will not take the initiative to change their situation because they are conditioned to a life of security, conformity, and conservatism, all of which may appear to give one peace of mind, but in reality nothing is more dangerous to the adventurous spirit within a man than a secure future.”

John Krakauer– Into the Wild

The Desert Fox, also known as the Fennec Fox is the smallest member of the species Canid. They can be found in the Sahara Desert of North Africa. Living in such averse conditions has allowed for some particular adaptations in order for them to find their way in their environment, most notably their prominent ears (I mean, look at those things):

The ears help them to dissipate heat, as desert temperatures can get up to 117 degrees Fahrenheit during the day. They also have a specially evolved set of kidneys allowing them to go without water nearly indefinitely and their required moisture can be obtained from their food. Unlike other foxes or canines, they have fur on the bottoms of their feet. This keeps them from burning their feet when traveling over hot sand. Their cream-colored coat helps to reflect the heat of the sun.

They are omnivorous, eating insects, lizards, and birds, but are also known to eat roots, leaves and other vegetation. The Desert Foxes are social creatures, live in groups, and mate for life.

I find this to be an incredibly encouraging little animal, finding home and company in a place where a large portion of its environment is actively trying to kill it. On days where I’m not sure how to find my own way, I often think of the Desert Fox. I find that I don’t have to worry about blistering heat, numerous birds of prey, even more numerous venomous snakes, or scarce food sources, and then I proceed to count my blessings and pray that I don’t become complacent in my station from lack of natural predators.

Because finding your way when there isn’t anything pushing you can be just as hard as navigating a desert full of bad things.

I was in Pittsburgh recently, taking an Uber to dinner. I’ve never particularly cared for riding Uber; it always feels like there’s an expectation for conversation and an uncomfortable and resentful silence if that expectation is not met. On one Uber ride in Manhattan there was a driver from the Caribbean who wouldn’t stop talking about his kid and showed my friend and I a video of him playing baseball. All this while driving in rush hour traffic. This most recent Uber ride was not that.

The man picked us up and the conversation was easy. After a little while of talking about what we were doing in the ‘Burgh, I asked him what he did for a living. He said that he had been a private investigator in Los Angeles for twenty years, from the early ’80’s to the late ’90’s. He said he had seen it all: cheating spouses, runaway kids, you name it. He thought it was all hilarious. He wanted to write a book.

His friends all thought his stories were great and they had been encouraging. The only problem, he said, was when he sat down to write he couldn’t get anything on the page. He just froze.

I know what this is. This is the crippling self-doubt that almost every writer and creative person I know deals with. Myself included. I told him so. Hell, I know a filmmaker who has a Crippling Self-Doubt Room in his house where he goes before he works on his projects. If you don’t find a way forward, you get stuck, and your ideas aren’t heard. Nothing happens and life goes on. You have to live with the sting of unrealized potential. That sting becomes more painful as the years go on and there is no more time to realize what could be.

The only thing to do, I told him, was to find a way to be with that debilitating feeling of self-doubt. Find a way to get something, anything, on the page. Once there is something on the page finding your way becomes much easier, and it can take you to surprising places. There is meaning in those places, satisfaction, and everything becomes a bit deeper and beautiful.

This is the lesson of the Desert Fox, a creature that has an unforgiving place to call home yet finds a way to thrive in it, and makes an existence in the uncomfortable. If there is something eating at you and calling to you, then you can always find a way to make it happen.

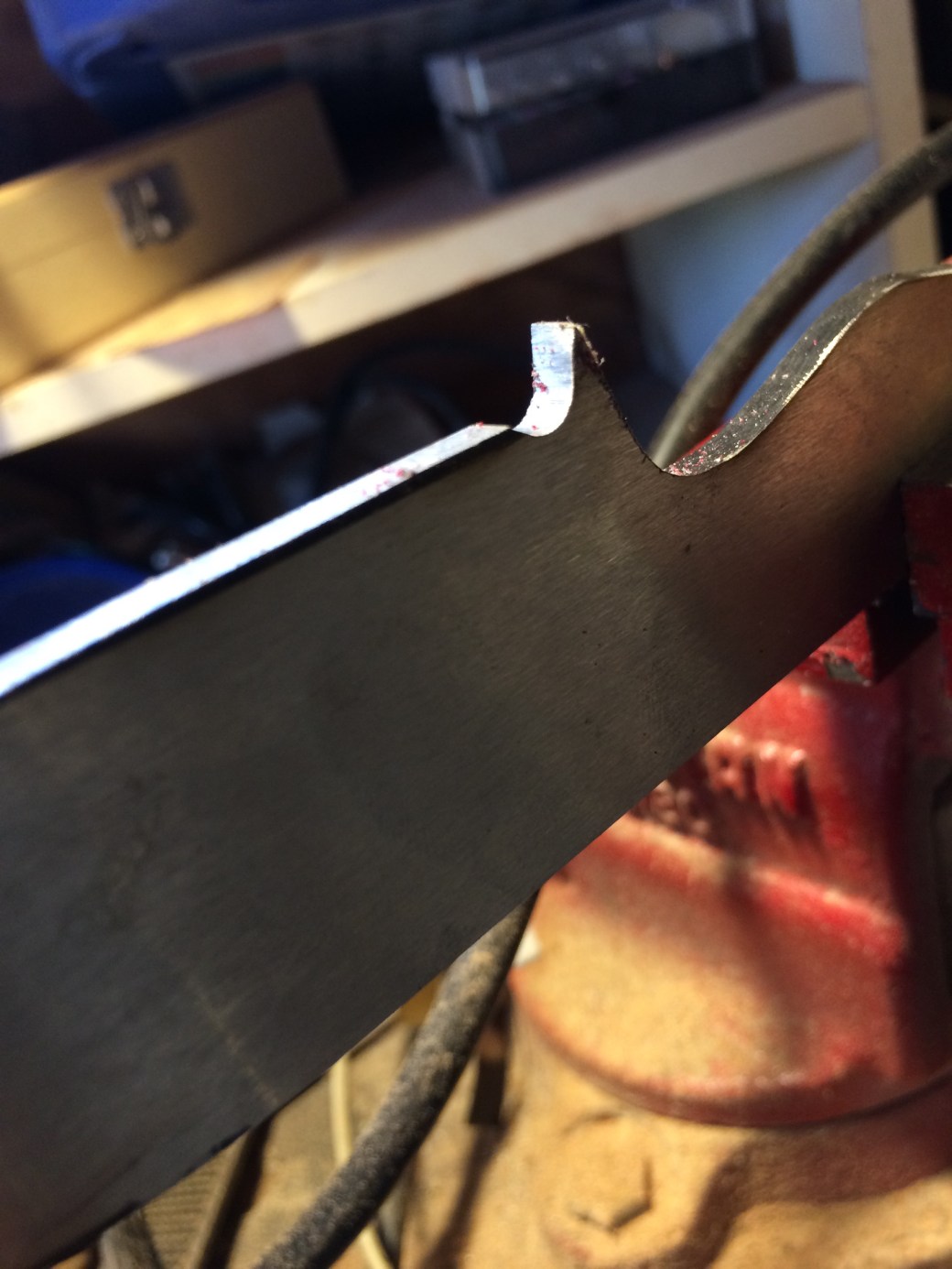

We start with flat stock O1 tool steel:

Roughing in the blade choil:

Profiled:

Rivet Holes:

Hand sanding the bevels before heat treat:

Hardened:

Tempered:

Hand-finished satin:

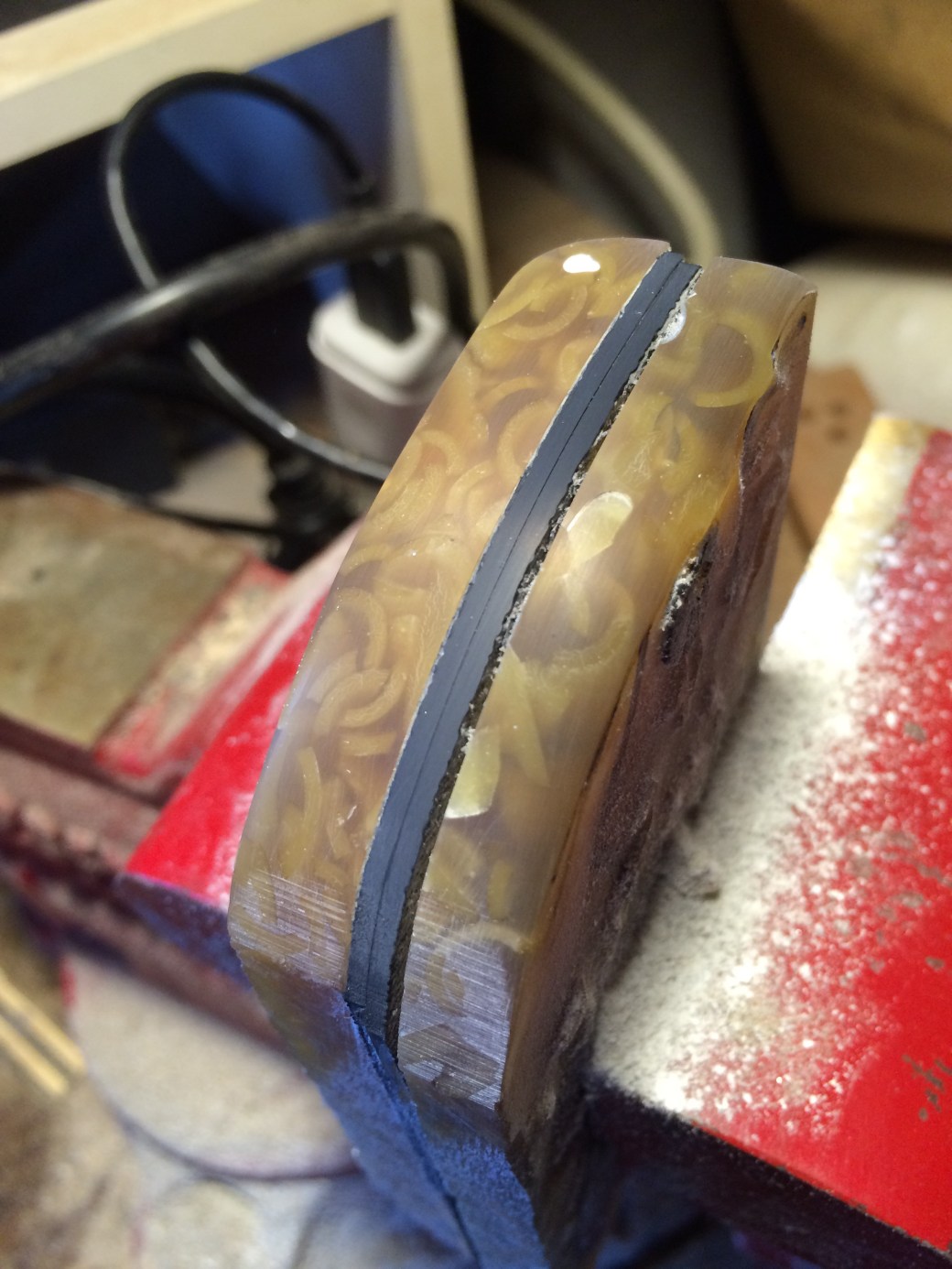

Texas Mesquite. One of my most favorite materials to work with:

Shaped:

Sanded to 220 before giving the grain a burst:

The Desert Fox:

If you can find a way to exist in the uncomfortable, than you can almost always find a way forward.

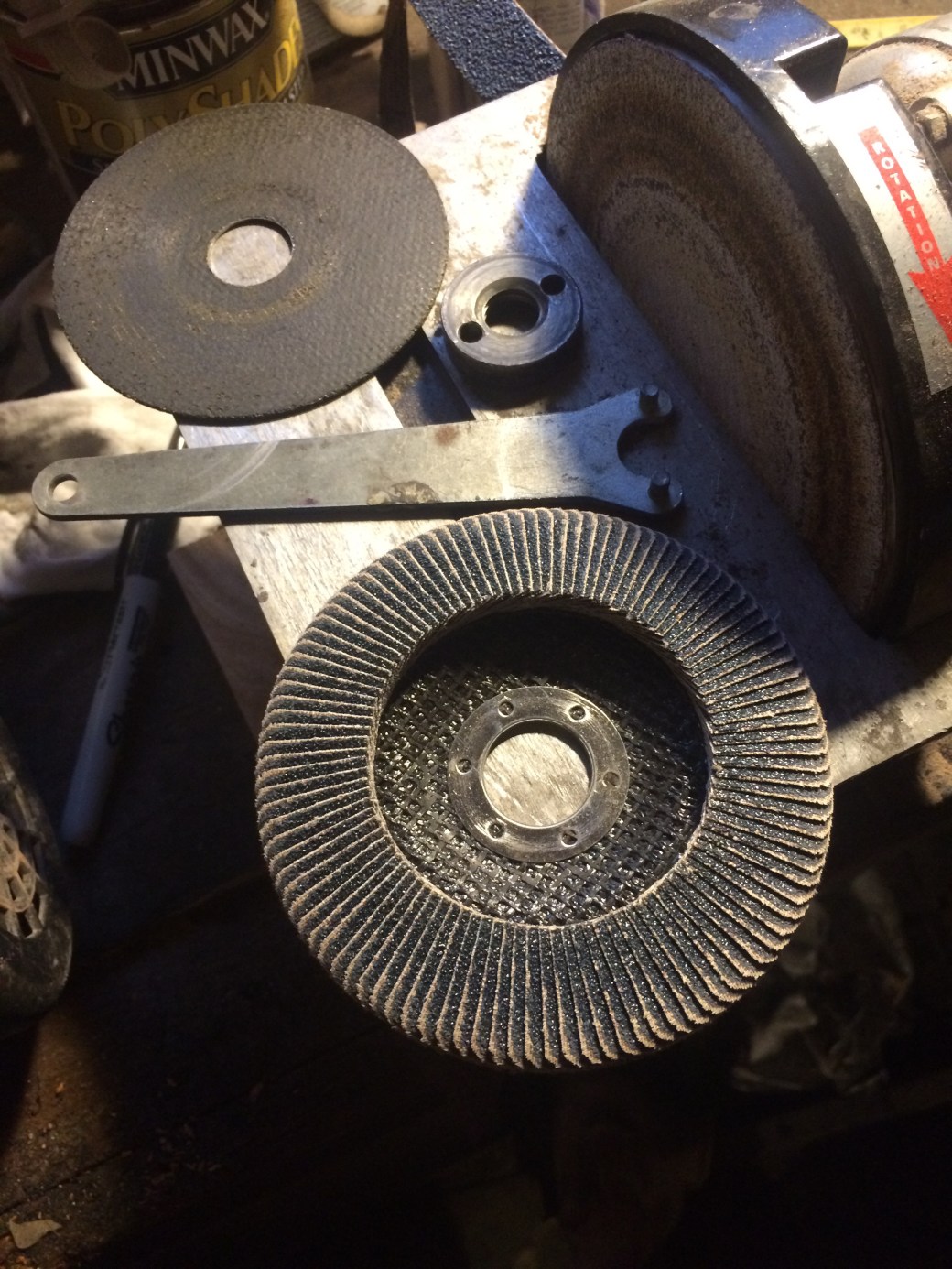

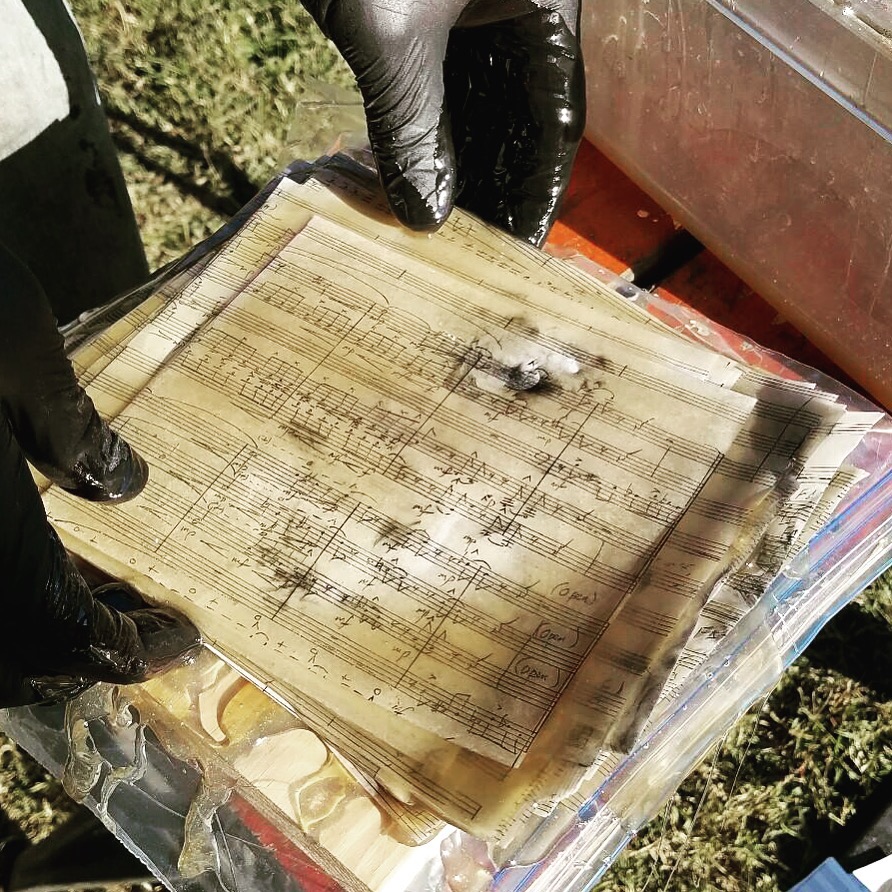

Blank for the Stuntjumper, with half inch holes drilled to lighten the load a bit.

Blank for the Stuntjumper, with half inch holes drilled to lighten the load a bit.