“ARMOR, n. The kind of clothing worn by a man whose tailor is a blacksmith.”

― Ambrose Bierce, The Unabridged Devil’s Dictionary

(you can read about the crafting of the original Archer here)

We all put on armor everyday. Some of us put on more than others. Sometimes it physically manifests. Hard hats, steel toes, wingtips, neckties. Some ladies refer to their makeup as war paint, another type of armor. Other times it’s more subtle and subdued- the way we carry ourselves, our use of vernacular in particular situations, and the image of ourselves that we present to the world. All these are things we do to protect ourselves.

A few years ago I had a temp job working construction over the summer. The company I worked for had a contract to build all of the temporary structures for the Boy Scout National Jamboree. I spent almost four months driving to a military base in the middle of nowhere. I use the term base loosely. It was really just a giant campground guarded by military police, and all of the campers carried semiautomatic weapons. In four months I used a flushable toilet maybe three times. The cast of characters I worked with were a colorful lot.

My boss was a Brazilian Jui Jitsu master. He got to work before everyone else and ran five miles on base. Some people have coffee before they start work. Our mornings with him consisted of tapping out of sleeper holds, arm bars, half nelsons, and doling out mollywhops of a variety I’ve yet to experience again.

One of the other gentleman did a ten stretch for first degree murder, which nobody found out till the work contract was almost up. The base knew he had a twenty year-old felony and vetted him for a base pass. I’m not exactly sure what this means, but military bases generally don’t mess around. He did good work and kept to himself. He was married to a florist and had a house in the country.

Then there was the gentleman who had just gotten out of jail for beating the the hell out of a guy with a tire iron. He was drunk and thought the guy was stealing his car. He was there trying to pay off the lawsuit and lawyer’s fees.

Another gentleman I worked with had severe anger management issues and was there because he was dating the company owner’s daughter. He had a degree in English and was trying to get into law school.

There was Jose from El Salvador who had four children and was still madly in love with his wife. He taught me filthy things to say in Spanish.

There were two football players on break from a small conservative college. They said they were there earning beer money.

Then there was me. My car had died and I needed to buy a new one.

I spent four months with these guys, riding around in the back of a decommissioned deuce-and-a-half, building things, and hearing stories that I’m still not sure if I believe or not. In these sorts of work environments a decent amount of posturing and exaggeration is to be expected from almost everyone. Despite their checkered backgrounds, these guys were not terrible to work with. Nothing felt unsafe except for the blistering heat, the bird-size mosquitos and the morning mollywhops to which I became adept at parrying.

Just to be safe I would put on some armor everyday- a bit of bravado, a bit of flash, a bit of the grandiose. My nicknames reflected that. The Viking. Sledgehammer. Red Devil. I was lifting a lot of weights and I was not a small man. It helped enforce some social boundaries. At the end of the day I could usually take it off, or so I thought.

The type of armor a lot of these guys wore- they couldn’t take it off. This was how they lived and you could feel that they had worn this armor for a very long time, so much so that it became a part of their being. There were scuffles, gruff talking, machismo. Everything was laced with an extra scoop of testosterone.

When you wear heavy armor you are shielded from many things that can hurt you. The drawback is that you shield yourself from the things that help you as well. You block out grief but you also block out the serenity that in time comes with it. You block out pain but you are also blocking the healing that follows. You can become a shell of yourself. The armor becomes limiting. You can’t move and you become horribly stuck.

What happens when you do decide to take the armor off? When you aren’t hiding behind any sort of bravado or grandiosity or gestures or facades? There comes a point where it becomes more painful to live with the armor on than off. You take the armor off and let the world in. All of it. The world becomes overwhelming. You’ve put on a different set of armor, something that allows you to breathe and move and serves you in a much deeper capacity.

This is the lesson of the Archer. To lightly armor yourself so that you are protected, yet you can still hit your marks with a deadly precision. You can move farther and faster and feel much more deeply. You become more aware and but find that you require a different sort of care for yourself and this may feel foreign. You feel pain more acutely but the healing becomes more available to you. The things you put out into the world feel more genuine.

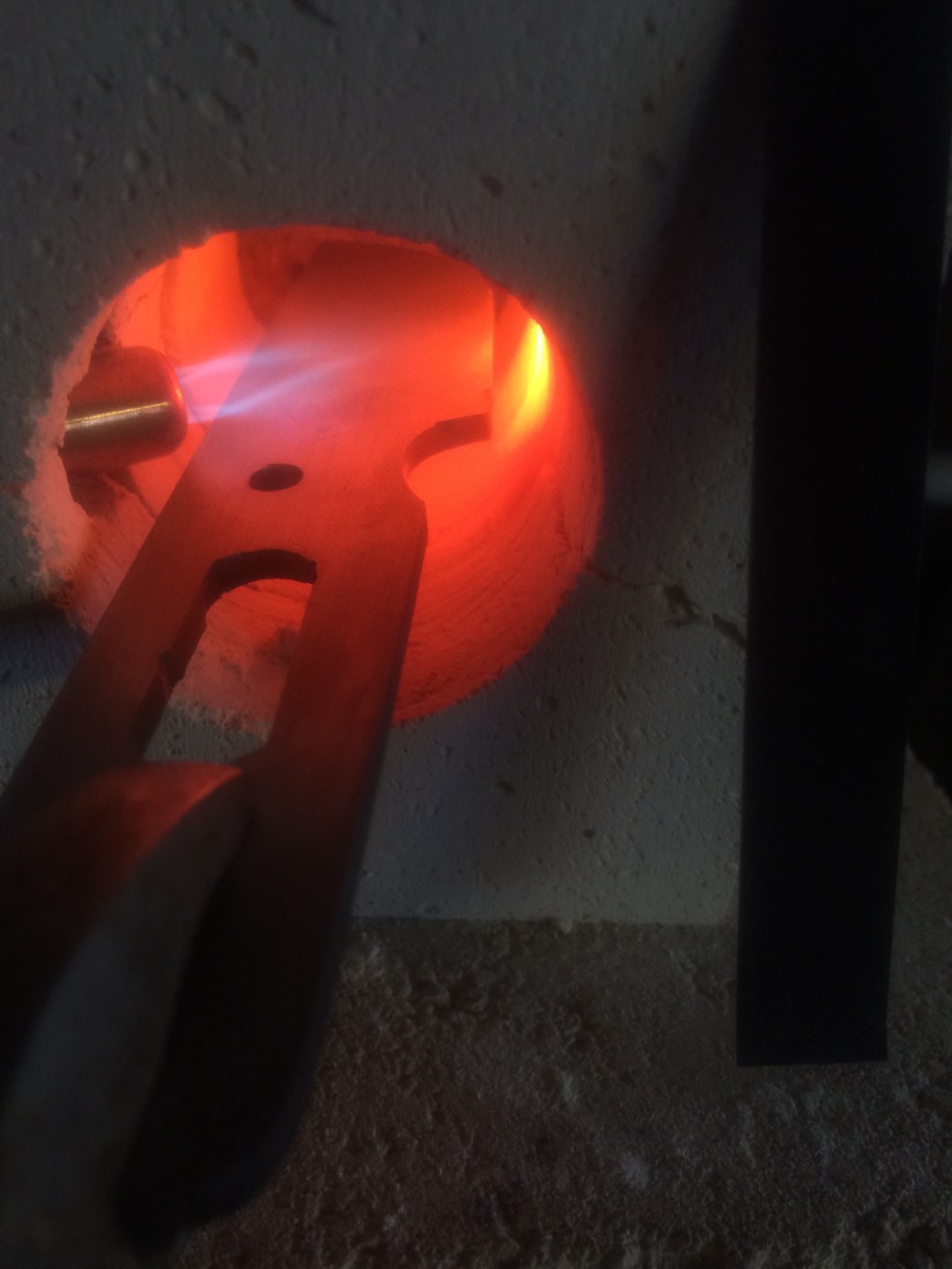

For this blade I wanted something long, sharp, and elegant. I designed her for the kitchen. She is ground thin and a bit more fragile- at one point I dropped her on the concrete floor and the tip blunted a bit. After a bit of grinding she was alright.

The Archer, Mark II: 1095 spring steel, Sapele handle, brass hardware

Take your time and adjust to this new armor as the world opens up to something beyond posturing and mollywhops. This is the deeper lesson of the Archer.