“Warrior,

The bite marks soon will heal.

Warriors do not forget how it feels”

Stepdad- Warrior (Jungles Pt. 2)

(This is the second part of a story. You can read the first part here).

On a late afternoon in mid July of 2018, three weeks after I nearly removed two of my fingers on a table saw, I found myself sitting with my girlfriend in a an empty group physical therapy room in a wing of the orthopedic center that had performed my surgery. My hand had been repaired: a third of my thumb amputated and my index finger wired together to fuse the shattered bones and blown-out joints into one piece.

I had been ordered to physical therapy by my surgeon for two-part treatment. The first part was wound care. This would ensure that everything healed as it was supposed to, with no infection or complications, and to keep scar tissue to a minimum. The second part was the actual physical therapy, to regain as much use as possible in my injured hand, which which was currently completely bandaged with only my pinky and ring finger exposed.

I didn’t protest. Nobody really talks about the aftermath of surviving something awful. It will take the fight right out of you. There is a truckload of emotional baggage that comes after the ‘get well’ flowers have wilted, the care cards have been boxed away, and normal life begins to resume. Bills pile up and normal work responsibilities resume, but you are still fragile and adjusting and most likely carrying the weight of trauma. Despair, depression, and existential crises of a behemoth magnitude are very real aftermaths of life-altering health emergencies as well as the emotional, physical, and financial burdens contained therein. All of this greatly lowers your resistance, and I found myself more than willing to do what I was told.

This included a mountain of paperwork filled with verbiage of responsible parties, guarantors, and out-of-pocket maximums, essentially telling me that I would be paying for all of this for a very long time. My girlfriend filled most of this out for me because I couldn’t even button my pants at that point much less sign my name.

In this room filled with all sorts of proprietary rehabilitative contraptions, I was introduced to Steve, an orthopedic hand therapist and educated hillbilly from West Virginia. He was assisted by Justin, a former football player and mammoth of a man who was getting a Masters in Occupational Health and working in the office for the summer. Normally this therapy room would be filled with patients but as it was late in the afternoon, it was just the four of us.

I found out, firstly, that hand therapists was a career that existed, and secondly, and paradoxically, they were the kindest sadists I had ever met. As we sat down to remove my surgical dressings Steve told me that we would be spending a lot of time together and it was going to hurt a lot, starting immediately. Boy he was right. It took him half an hour to get the surgical dressing off as it had fused to my skin and surgical wounds with dried blood and other fluids and had two weeks to calcify to my skin and raw flesh.

Pain, as I would slowly learn, is an extraordinary teacher. It reveals things about yourself that you most likely didn’t know were there, provided you lean into it a bit. So I leaned in. Steve was unrelenting and asked how I was doing. I told him it hurt like a motherfucker. “Great,” he said, “let’s keep going.”

When he finally disrobed my fingers I couldn’t look at them. They looked like raw hamburger that had been stitched up. I felt a little nauseous and so did my girlfriend. Steve, however, said everything looked great and as it was supposed to look. He bandaged my index finger and what was left of my thumb individually with inch-wide gauze dressing. I was told to come back the next morning to get fitted for splints to protect my healing fingers and instructions for bandaging.

My girlfriend and I left and got Bojangles. Bojangles chicken had become part of the healing process after one of my pre-operative visits several weeks before. While the surgeon was concurrently examining my mangled hand, making a surgery plan, and giving me nerve block shots through massive syringes, my girlfriend was holding my other hand and staring away from the carnage and at a stack of magazines across the room. There was a Southern Living magazine on a nearby table with biscuits on the cover. “We need biscuits”, she whispered to me. This was a welcoming distraction because I immediately stopped thinking about my hand and how much all of this was going to cost and thought about the glorious coming of biscuits and fried chicken. From that moment on Bojangles became Orthopedic Trauma Chicken: the patron saint of reconstructive hand surgery, may her light ever shine upon us.

(Many months later one of her children broke their wrist and the other dislocated his knee. They too learned of the virtues that Orthopedic Trauma Chicken offered.)

The next day I went back to the office early in the morning by myself. Steve was waiting for me with some sterile wraps. He explained to me that the bandages would serve as an infection barrier, but also to help my fingers to keep their shape as they healed, specifically my thumb. In this early part of the healing process, he told me it was important to wrap them as he had shown me, as that was the desired shape that they would take. I wasn’t to wash them or put any balms or ointments or disinfectants on them. The body takes care of itself, he said, and I was to let my body do it’s thing. Infection was a dangerous possibility and I was to call them if I showed any signs, but the 2,000 milligrams of antibiotics I took everyday kept that from happening. I did exactly as I was told. I left with two bright blue removable finger splints made from a thermo-setting plastic. I could button my pants again.

I went there two or three times a week after work. It was always in the late afternoon and usually only a couple people were in the therapy room. Steve would unwrap my fingers and let them air out. Justin would bring a small cup of water cut with peroxide that I would soak my fingers in for about half an hour. Steve would then pick off the eschar with forceps to prevent scar tissue from forming. Every few days he would remove a couple of stitches. All of this was extremely painful and it went on for a month and a half but I was so glad for those two guys. Steve would tell stories about the dumb things he did in the boonies of West Virginia growing up, and Justin would regale us with stories of dancing on the bar of a downtown drinking establishment. Justin also had excellent playlists that he would have going over the speakers. I came to really look forward to these appointments.

As I sat there soaking my fingers day in and day out I also noticed some other other patients there. There were several gentleman with work injuries who were there on their company workman’s compensation. There was a lady who had damaged a tendon in her hand with a kitchen knife, and a couple ladies and gentlemen with wrist injuries. Steve and the gang tended to all of them. There was one gentleman who stood out- a large muscular guy whose injury I couldn’t figure out. I knew he wouldn’t be there if he hadn’t had something serious happen but I couldn’t discern what that was. One day as I was sitting with my hand airing out waiting for Steve, I heard somebody tell me how good my fingers looked. It was the large gentleman who came in everyday. This surprised me because for one; I felt that despite what everyone at that office was telling me, my fingers did not look great and that I was a disaster, and for two; I wasn’t used to talking to anybody but the therapists outside of small pleasantries.

The large man then showed me his left hand and I saw that he only had four fingers. His thumb was nothing but a nub and his index finger and the flesh immediately below was completely gone. I had to look twice because it was so completely normal and comfortable for him that I didn’t notice at first. Amazingly enough, that wasn’t even why he was there- he was an electrician by trade and had torn a major tendon in his bicep that had to be reattached. His hand, he told me, had happened after an accident when he was nineteen years old. The surgeon had saved his index finger, but he said he had it removed a month later because he was pissed off that it wouldn’t work right. Young and dumb, he told me, and he wished he had kept the finger and learned to use it as it was. He told me to figure out how to work through the pain and get as much use out of it as possible.

……..

While all this was happening I was going to work, and sorting out the massive stack of bills I had accumulated. Even with insurance, this whole ordeal was phenomenally expensive. I learned more about the financial workings of the healthcare industry than I ever cared to. Shortly after the surgery, which was covered by my insurance, I got a $4,000 bill from the anesthesiologist, saying it was an out of network provider and not covered by my insurance. After spending hours on the phone with the insurance company, the surgery center, and the anesthesiologist, I found out that it should have been lumped in with my surgery but wasn’t. The reason for this was because the tax ID for the anesthesiologist’s claim was in-network, but the provider they sent wasn’t. All three of them told me I was stuck with this bill and there wasn’t anything they could do for me. Through some stroke of fate, I found that my neighbor worked in insurance and knew the billing manager of my surgery center and gave me her number. I spoke with her once and I don’t know what she did but she waved her black magic healthcare wand and made it go away. That was just one incident of many, but it was always a whiplash. I renamed my mailbox the Mailbox of Doom because I never knew what fresh hell was going to be waiting for me.

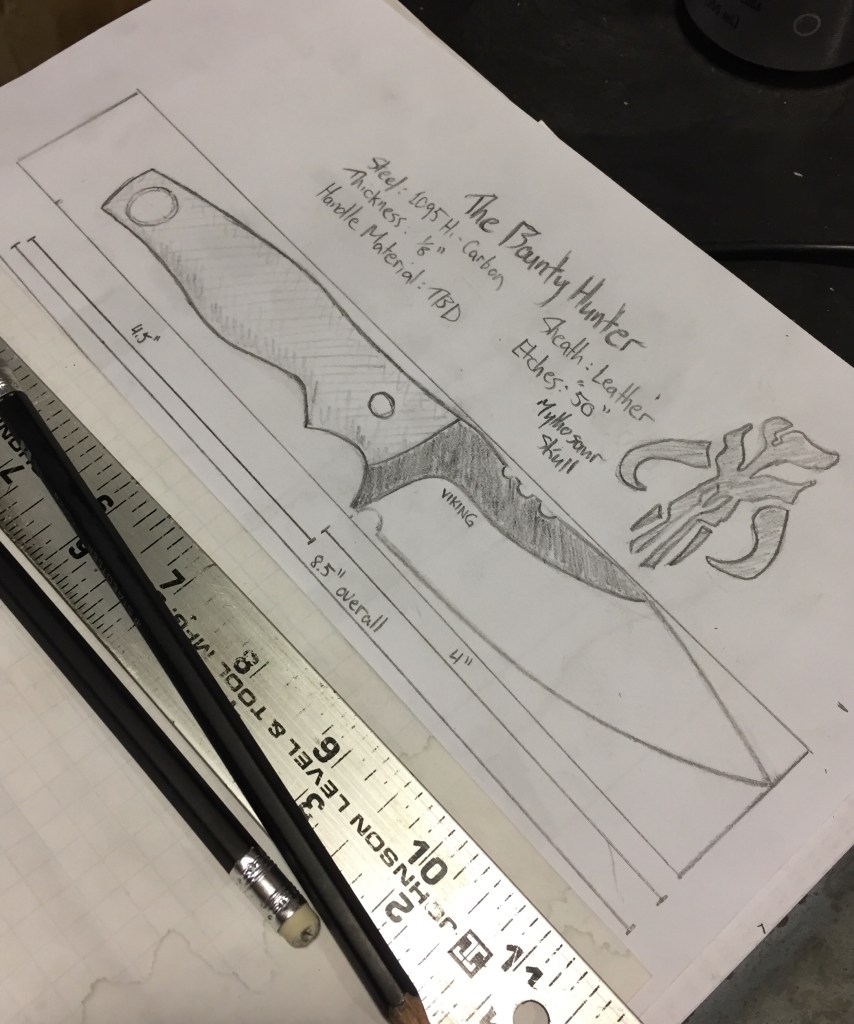

As my hand healed, I got back into the shop a little bit. Steve had told me that I would be able to do all the things I had done before, but I would definitely have to find different ways to do them. Finding those different ways added up to teaching myself to make knives all over again. I found myself thinking of a professor I had in music school. The man was a brilliant concert pianist. I didn’t find out till much later that he had suffered a stroke and had to teach himself to play piano all over again- I had no idea of this when I was taking class with him. The man had since passed and I found myself wishing to be able to ask him about what the rehabilitative process looked like for him and how it felt.

I also called my yoga teacher. I missed being able to do yoga and asked Steve what I could and couldn’t do. He told me I could put weight on my forearms, but not my hand. I told this to my yoga teacher and she choreographed a modified Ashtanga series for me that I could do on my forearms. She told me to get some yoga blocks to help facilitate this. When I saw how much foam yoga blocks cost, I decided I would just use a piece of treated 4″x6″ lumber cutoff that I had in my truck. I did Viking Recovery Yoga a couple times a week and it was brutally difficult. I leaned into the pain.

……….

Slowly I eased into more physical therapy work and getting facility back into my hand. Justin had gone back to college and I often met with another therapist, Kay, a lady from Puerto Rico. She was fantastically kind and gentle, and always wore fiercely hip shoes. Her husband was retired military and they went on wild adventures on the weekends. She showed me pictures of a trip where they had taken visually impaired kids on a whitewater rafting trip- all the kids in the picture are tearing ass down river rapids and had on the giant sunglasses that you see the elderly wearing. At first I wondered how she functioned in such a deeply masculine work environment but the reality was that she was probably the wildest of everyone.

With Steve, I always took a ‘make it suck more’ approach to physical therapy. Make me do more, give me more things to work on at home, kick my ass a little harder, I’ve got to do better. With him it was like being at the gym with a buddy. While I was working through my brutal hand exercises, he would be timing me and telling me about his last bow hunting adventure. One time he had me dig twenty marbles out of five pounds of silly putty with my two gimpy fingers while he went on a soliloquy about a regional restaurant chain in West Virginia with the best damn breakfast biscuits he had ever had.

With Kay everything was a little bit gentler. I still pushed but the drive was more subdued. Conversation was turned inward and bravado was dialed way back. She asked about how things were going in the shop and I would do my best to articulate all the digital nuances I was navigating and modifying. My type A disposition would be disarmed before I even knew it was happening and she would talk me through issues I was having. It was a lot. After I had spent forty-five minutes struggling with an exercise, she would always tell me I was doing really well. I would then go sit in my car and cry before I drove home.

……..

In December I had another smaller surgery to remove the hardware that had been in place while the bone in my index finger fused. Compared to everything else it wasn’t that big of a deal. In February of 2019 I had my last post-op follow-up with my surgeon. Before he discharged me from his care and the care of the physical therapists, he told me I had healed very quickly and my results were not typical of people who sustained my severity of injury. I told him that I didn’t have a gold plated insurance plan and zero workman’s compensation. If I gave up I would just sink. There was no other choice.

I also told him that there were a lot of people who had invested a tremendous amount of time and energy into a very expensive process to help me, and it would be a huge disservice to everyone, including myself, if I didn’t honor that by doing the best that I possibly could.

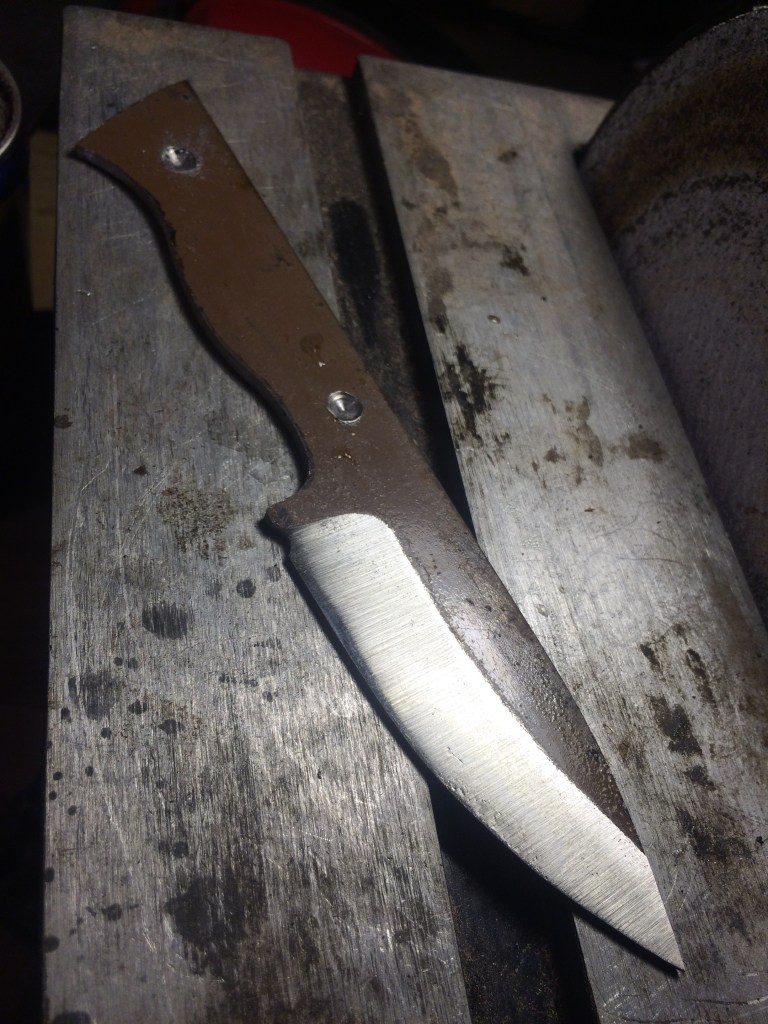

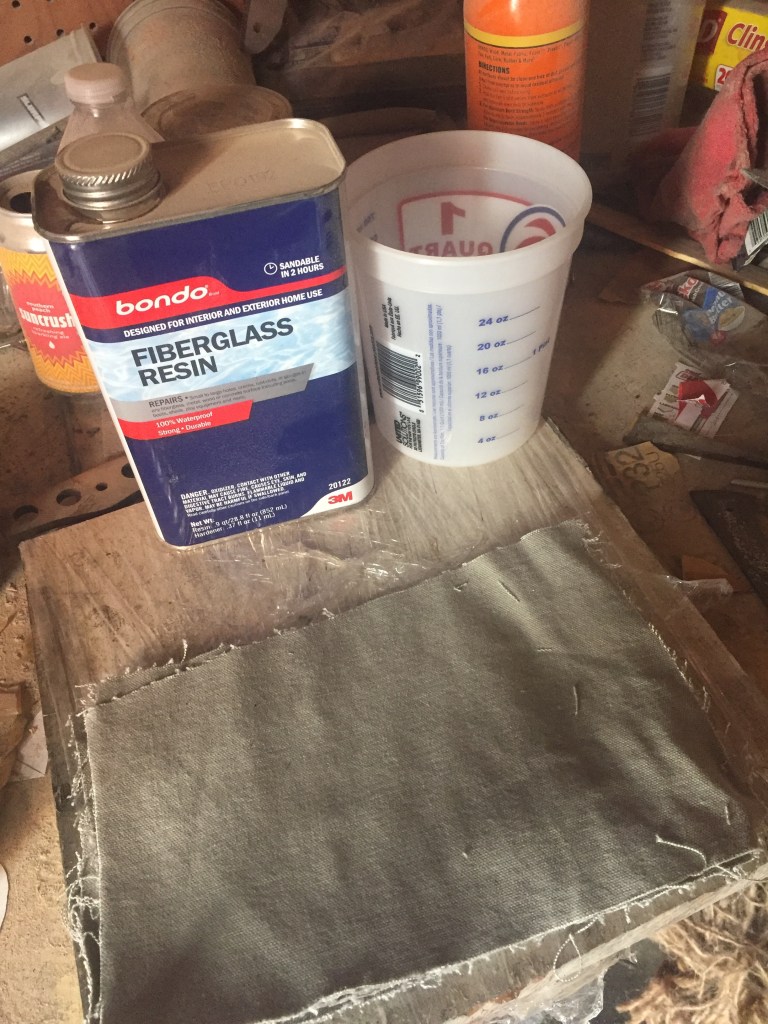

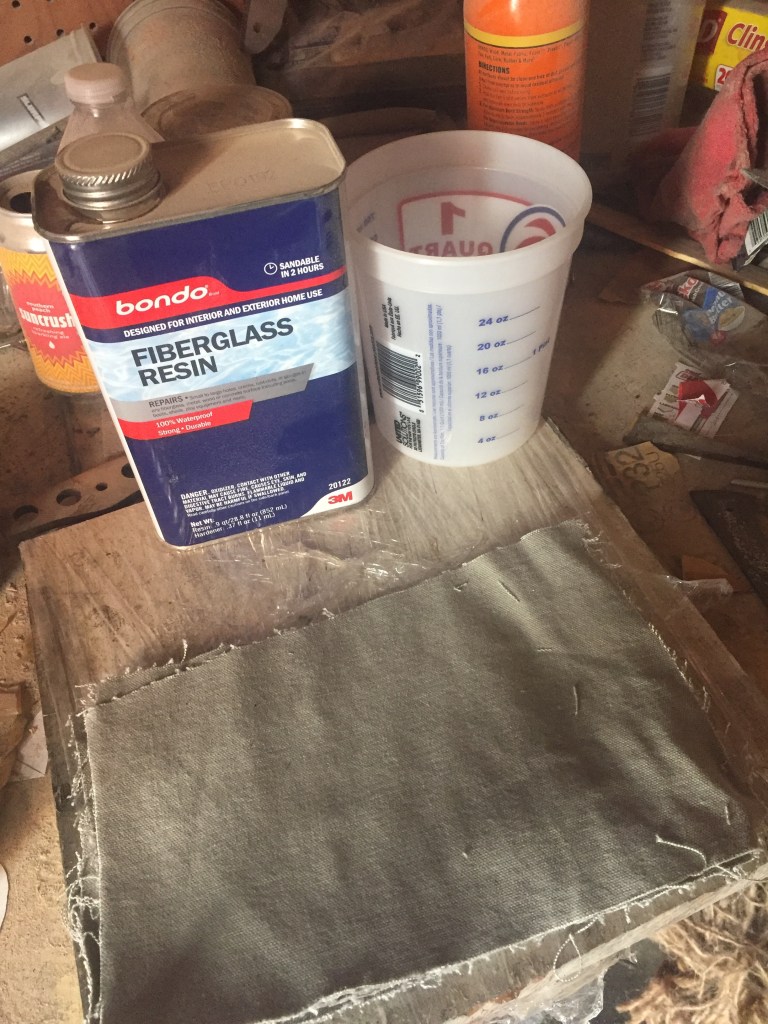

This was the first knife I completely finished after I was discharged.

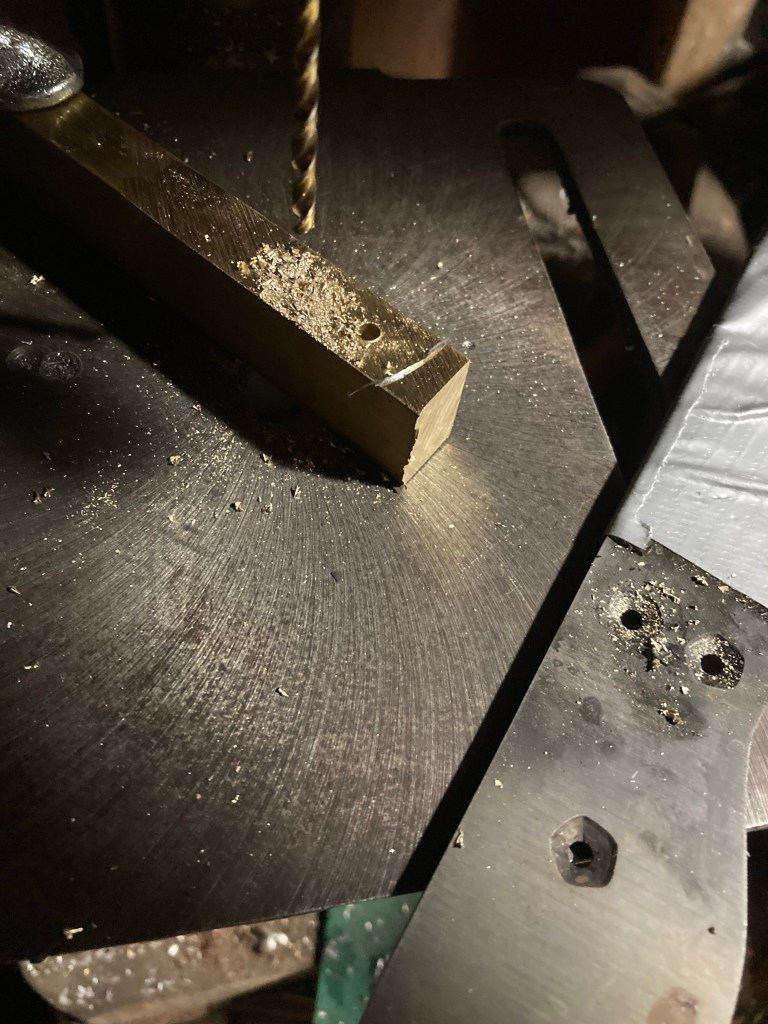

This steel came from a friend. The man they bought their house from made lawnmower blades and they found these in the garage when they moved in. This is a 1/4″ oil hardening steel:

Rough grinding:

Hand sanding before hardening:

Hardened

Tempering:

Satin finish:

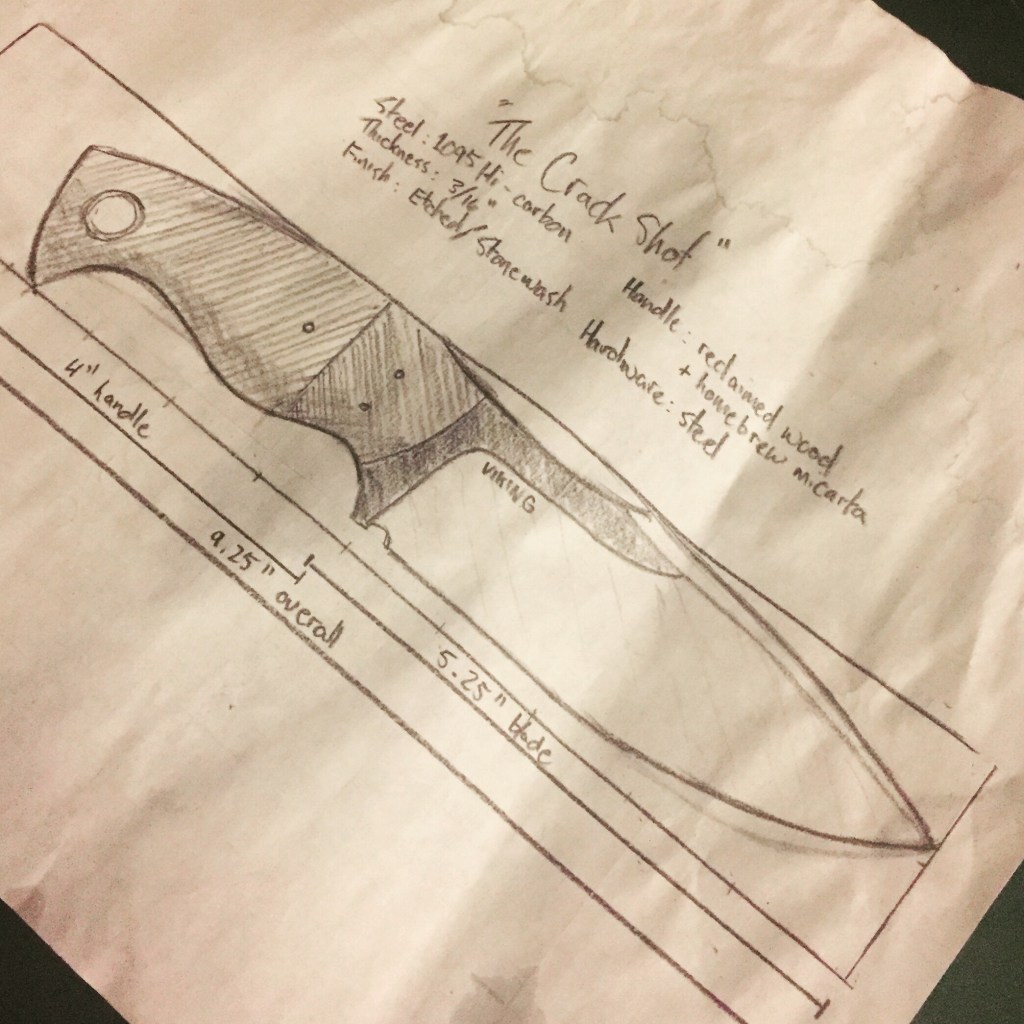

Spalted Pecan from my cousin in Texas:

The black lines weaving their way through the grain is actually a fungus. This fungus that injures the tree actually makes it more beautiful:

The Persuader:

Move on, but don’t forget how it feels.

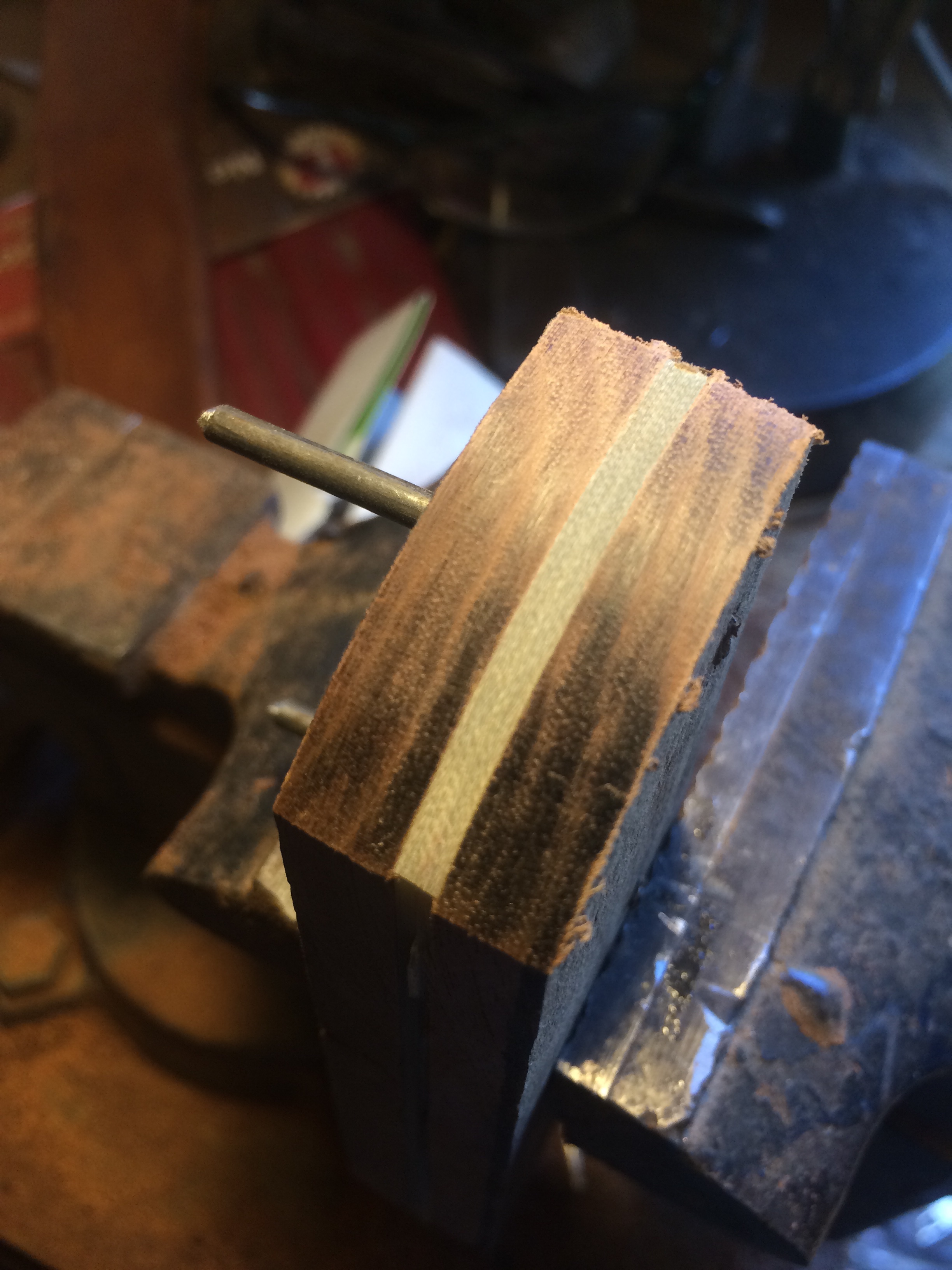

In a continued practice of saying ‘yes’ I chose to use some of the Black Walnut I got from the tree job for the handle material. It fit nicely into the story of these knives. This is what it looks like sanded and polished.

In a continued practice of saying ‘yes’ I chose to use some of the Black Walnut I got from the tree job for the handle material. It fit nicely into the story of these knives. This is what it looks like sanded and polished.