“I want to go back in time, because I’m a celebration in the making.”

― Francis Dunnery, “Autumn the Rainman“

About eight years ago I really needed a job. I had been fired from my previous job and had been piecing everything together for about 6 months. It was not going great. I was barely getting rent and health insurance paid and my girlfriend was getting ready to leave me. A friend of mine told me to give this small company a call- they were always busy and always needed good help.

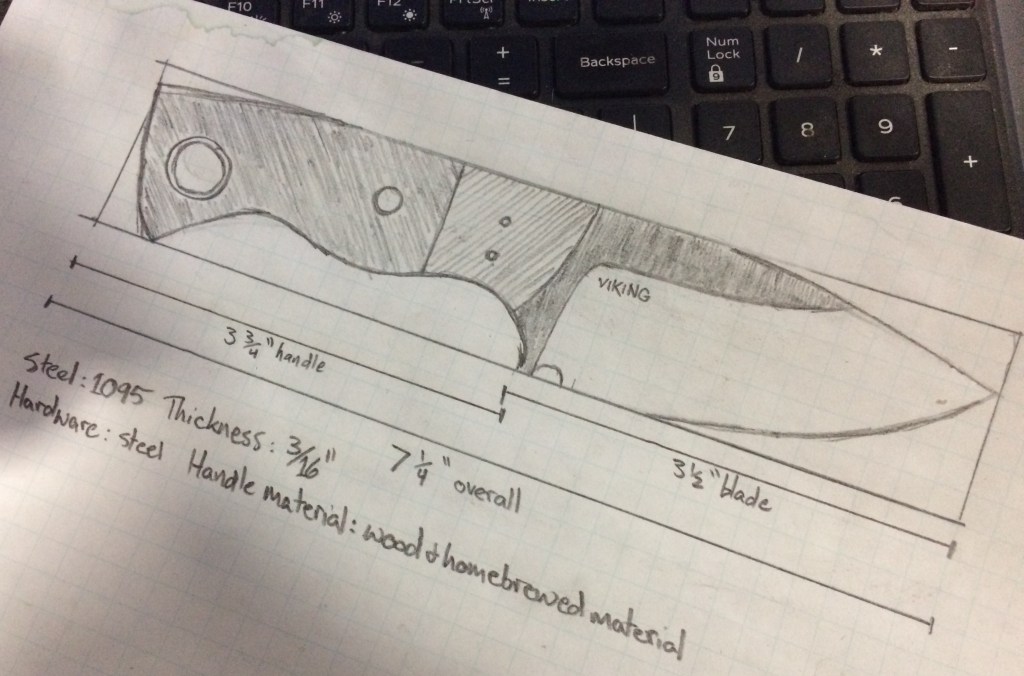

I called and spoke to the operations manager. I told the ops guy I was looking for a part time job- I had a small custom knife shop and I played music and I needed to have time to do these things. I think he probably thought I was a crazy person. He told me they didn’t do part time work but said I could send my resume and come in for an interview. Options were pretty limited at that point so that’s what I did.

I went in and did an interview. He told me this was a good place to work- the place did well. The gig looked insane. There was a warehouse slam full of skids of gear to be sold, and stuff everywhere. They looked super backed up. I don’t know if my resume was that impressive or I made an exceptional first impression or they just badly needed help, but I told him I could give him 3 days a week and he said OK.

So that’s what I did. I had two shop days a week and went in three days a week. I would build my schedule around getting into my shop, or doing crazy contractor gigs, or whatever I had to do to try and fill out my bank account. For the first two years I was afraid they were going to fire me but nobody ever gave me a hard time about it.

Within two months a being there they sent me to Atlanta to get some equipment for resale from a major client and make sure it all got loaded to get back to our warehouse. I hung out with a high level corporate engineer all day and we talked about knives and municipal engineering of their major corporate campus. Gear got back to our shop, and everyone was happy.

I did the part time thing for five years. Sometime during the pandemic everything started getting really expensive. My rent was going up about 30%, groceries were getting ridiculous, and I was seriously wondering how I was going to make ends meet. I was doing a lot of really interesting work but none of it was paying quite enough.

About this time the ops guy asked to speak with me. The company was doing well, but a lot was in short supply, including finding help. He asked me what it would take to get me there more. No pressure he said, but take a few days and look at my numbers and let him know what my time would be worth to be there more.

There were some good paying gig that I really enjoyed doing that were sort of dried up from the pandemic. There were other things I had been doing for over a decade that I was just kind of tired of. Honestly I had been trying to figure out a way to get out of some of the things I had been doing. I was doing really good work in the shop and playing a lot of really good gigs on the weekend. It felt OK to let those other things go.

So I gave the ops guys a number. Nothing crazy but a number that would buy me out of most of the stupid shit I was doing to make ends meet. He said not a problem. I asked him if I needed to write up a CV of the stuff I had been doing around there. He said no need, it was already handled. And that was that. I told him I kind of suck at company culture, and I’m kind of a combative employee but this place had been a good place to work and always kept me safe. They did things for me that they didn’t have to do, especially during the pandemic, and when all my other stupid jobs told me tough shit, figure it out.

Within about 4 months of getting a raise my credit score went up 300 points. I didn’t have to do stupid contractor work, I could focus on doing good work on knives, and I could play killer gigs all over the mid-Atlantic coast. Looking back I wished I had figured all of this out a decade earlier, but these are the paths that make us who we are.

…..

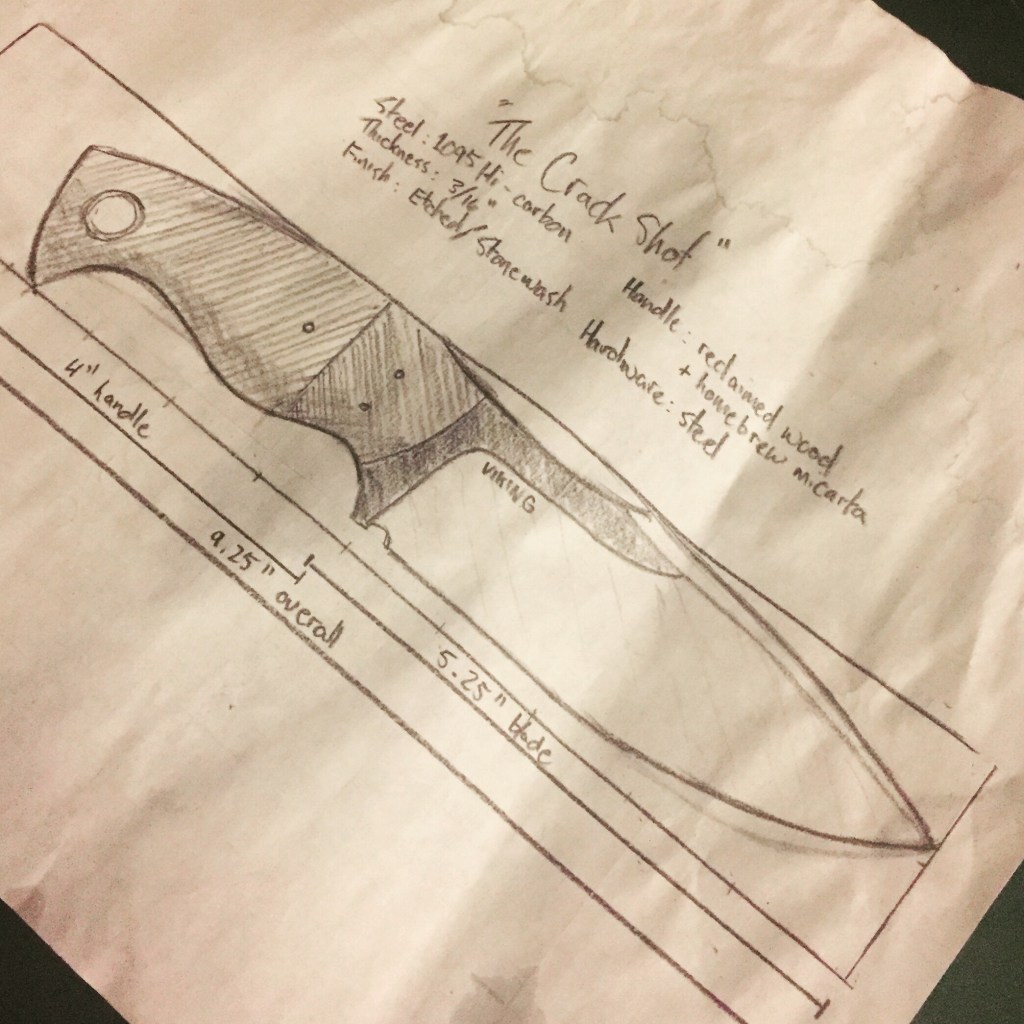

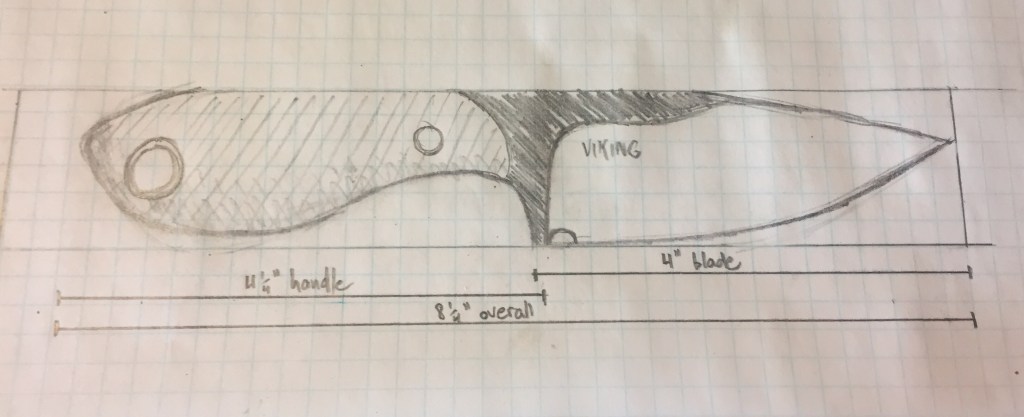

Sometime in September of this year the ops guys asked me if I could do a kitchen knife for his wife. It would be a tribute to her father. The way he spoke of his father-in-law I thought he was still alive. It wasn’t until about 15 or 20 minutes into the conversation that I found out he had passed twenty years earlier. I thought that was really special the way he spoke of the man and the affection that was there.

‘We just talk about him all the time,’ said the ops guy.

The ops guy had said his father-in-law was the sort of guy who could do anything and was curious about everything. He told me all these stories about the man, who was a representation of a generation passed. In his later life he lived in a trailer in the woods with half a million dollars worth of tools, automatic weapons, electronics, and gadgets.

We were talking about what to call this knife. He had bought an old machine shop sometime in the 80’s, and there were all these old work uniforms left in there, which he started wearing. They had nametags stitched on the shirts, all of which said ‘Bob’. So even though his name was actually Roger, everyone called him Bob. I told the ops guy we absolutely have to call this knife ‘The Bob’. These are the sort of special builds that makes this craft worth doing.

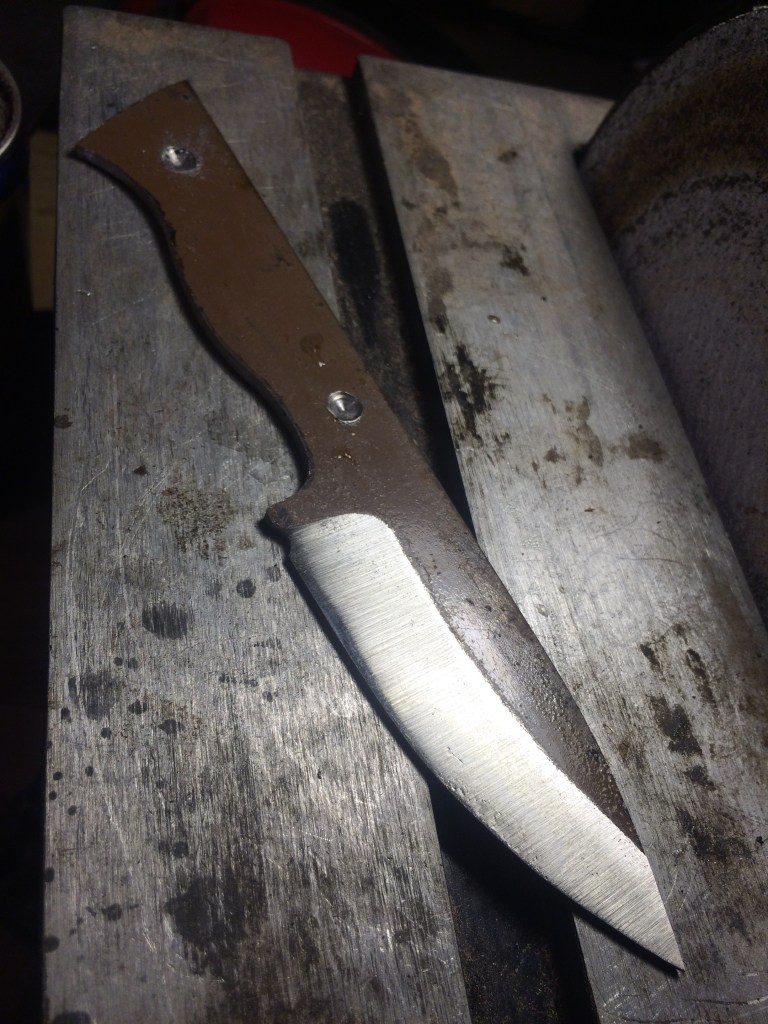

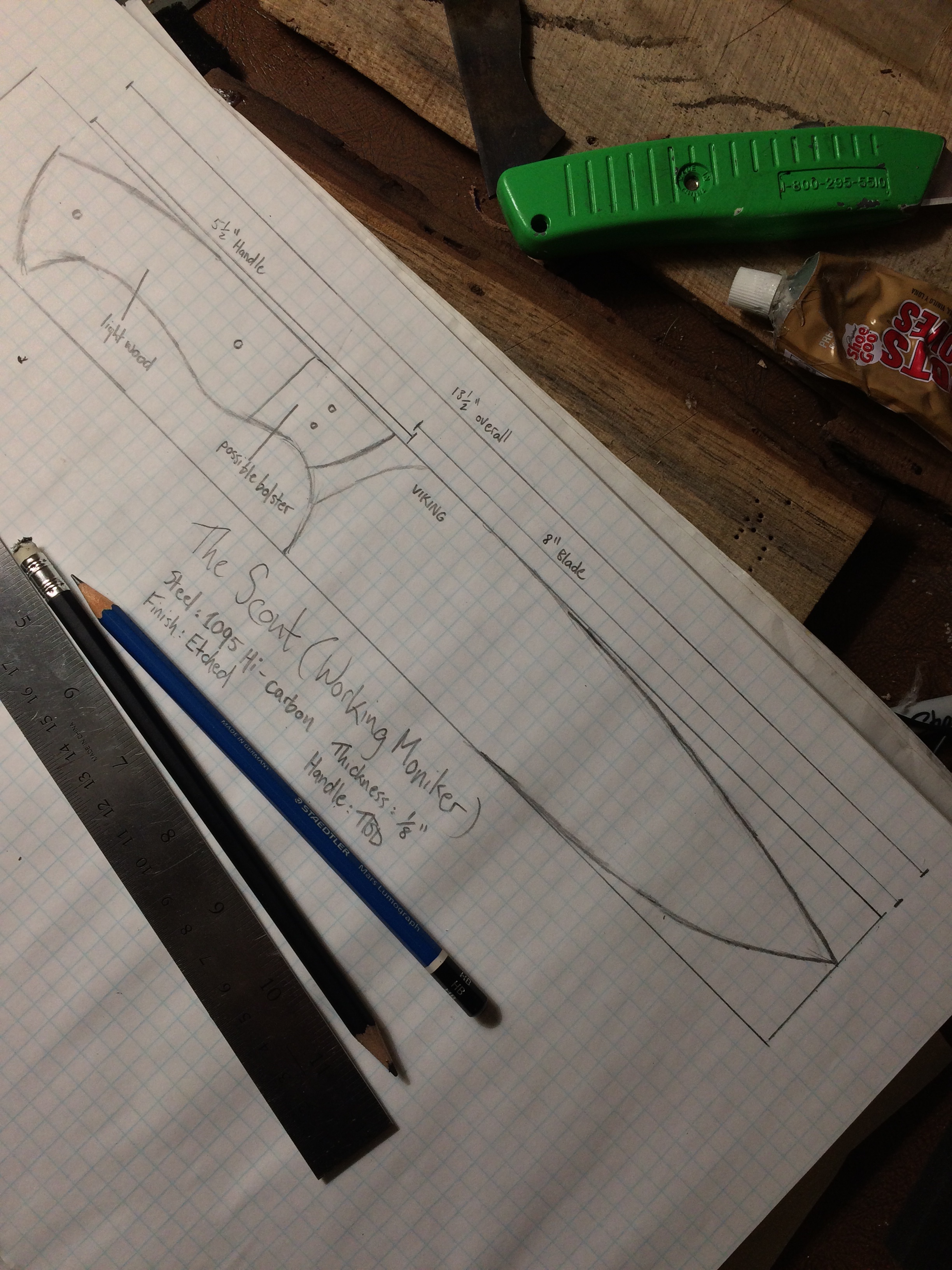

They still had Bob’s work clothes, and allowed me to make them into a handle material. Turning this man’s possessions into handmade kitchen tool to be used everyday seemed the best way to celebrate this man that everyone held dear. I started with a 8′ chef knife design:

Template is made

Drilling the rivet holes. I like to put a countersink in about a third of the way through the thickness of the steel on either side. This will allow for a bit of play during fit-up and ultimately makes for a tighter fitting handle.

Blade profile is cut and smooth.

Centerline is scribed. The cutting edge is intentionally left thick and will be ground thin after heat treat.

A bit hard to see but I have put a radius on the spine. This will make for a more comfortable pinch grip. If you are a chef swinging one of these for 8 to 10 hours a day, a square edge can lead to bruising on the index finger.

Ready for the forge. I’ve removed a bit of material while the steel is soft to establish the bevel. It will make it easier to get an even grind once the steel is hard.

I harden the blade before it is fully ground because long and thin blades like to warp and crack when heated.

Quenched. She is nice and straight with no cracks.

Full flat grind. This is off the grinder at 220 grit.

Hand sanding to remove the machine marks. Windex helps the sandpaper cut better.

Satin at 400 grit. Ultimately this finish took about two hours per side.

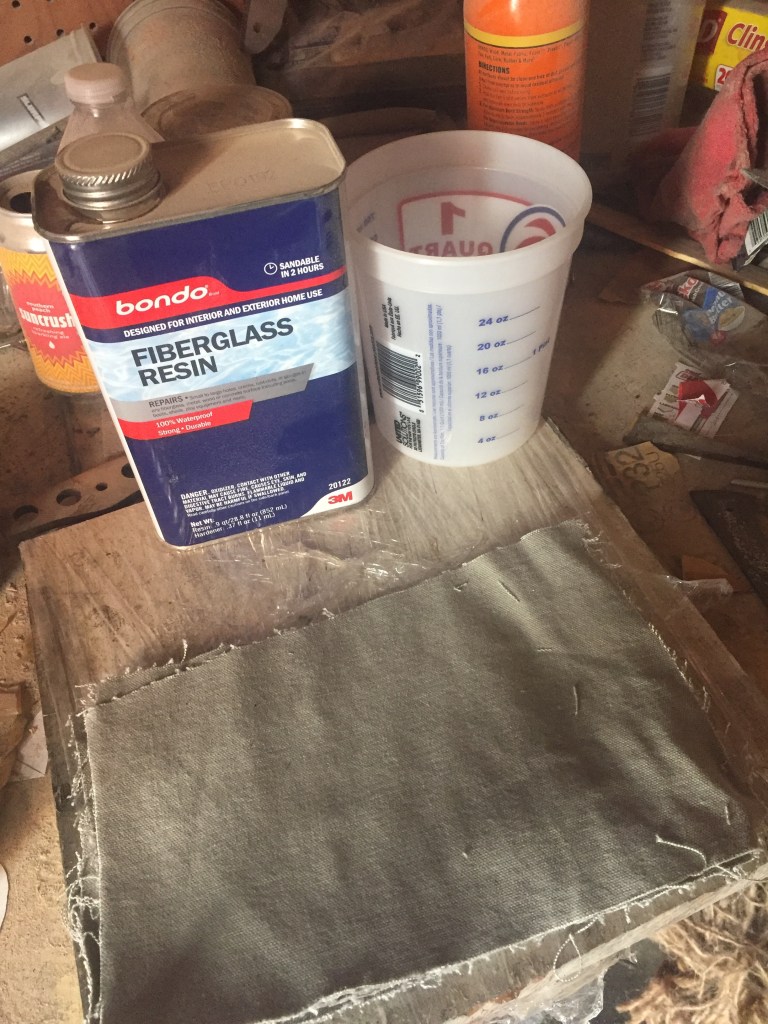

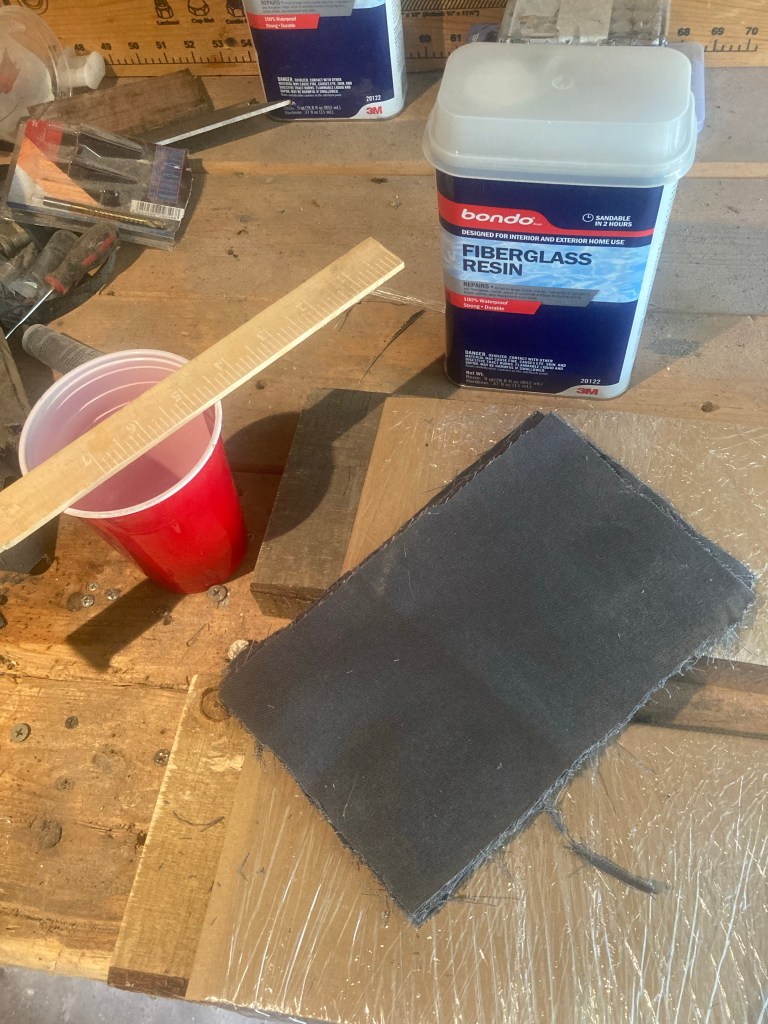

Handle time. Bob’s work clothes. Mostly polyester, which will give a more defined ‘grain’ on the final product.

Getting everything cut up into uniform pieces. It’s impossible to find good help these days.

Mise en place

As each piece gets stacked, fiberglass resin gets spread. This will turn about 16 pieces of Bob’s pants into one solid slab that can be worked and polished.

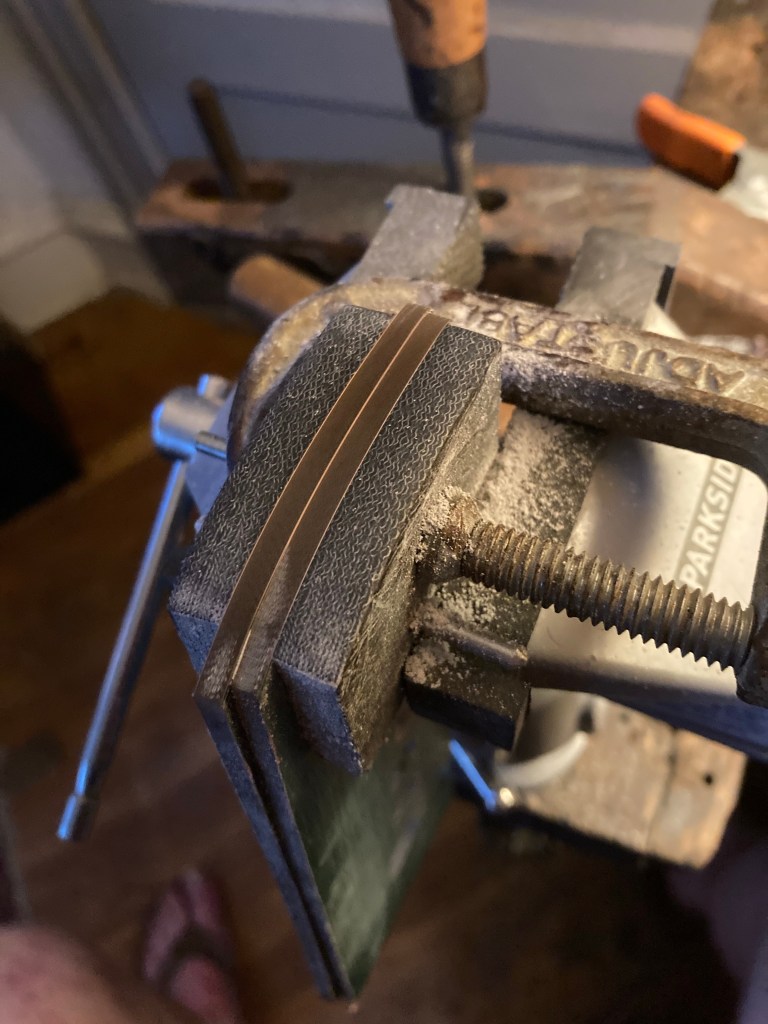

This gets clamped up. We want to smash everything as evenly together as possible. As the resin cures through the porous material everything will bond together.

I always mix a little extra. Fiberglass resin is an exothermic polymer and will naturally heat up as everything starts to catalyse. The melted cup tells me the mixture is curing properly and I mixed everything correctly.

Turned out nicely with a tight grain.

We follow the same process for Bob’s work shirt.

This material is a little thinner, so we try to do more layers.

Everything did what it was supposed to.

This also turned out nicely.

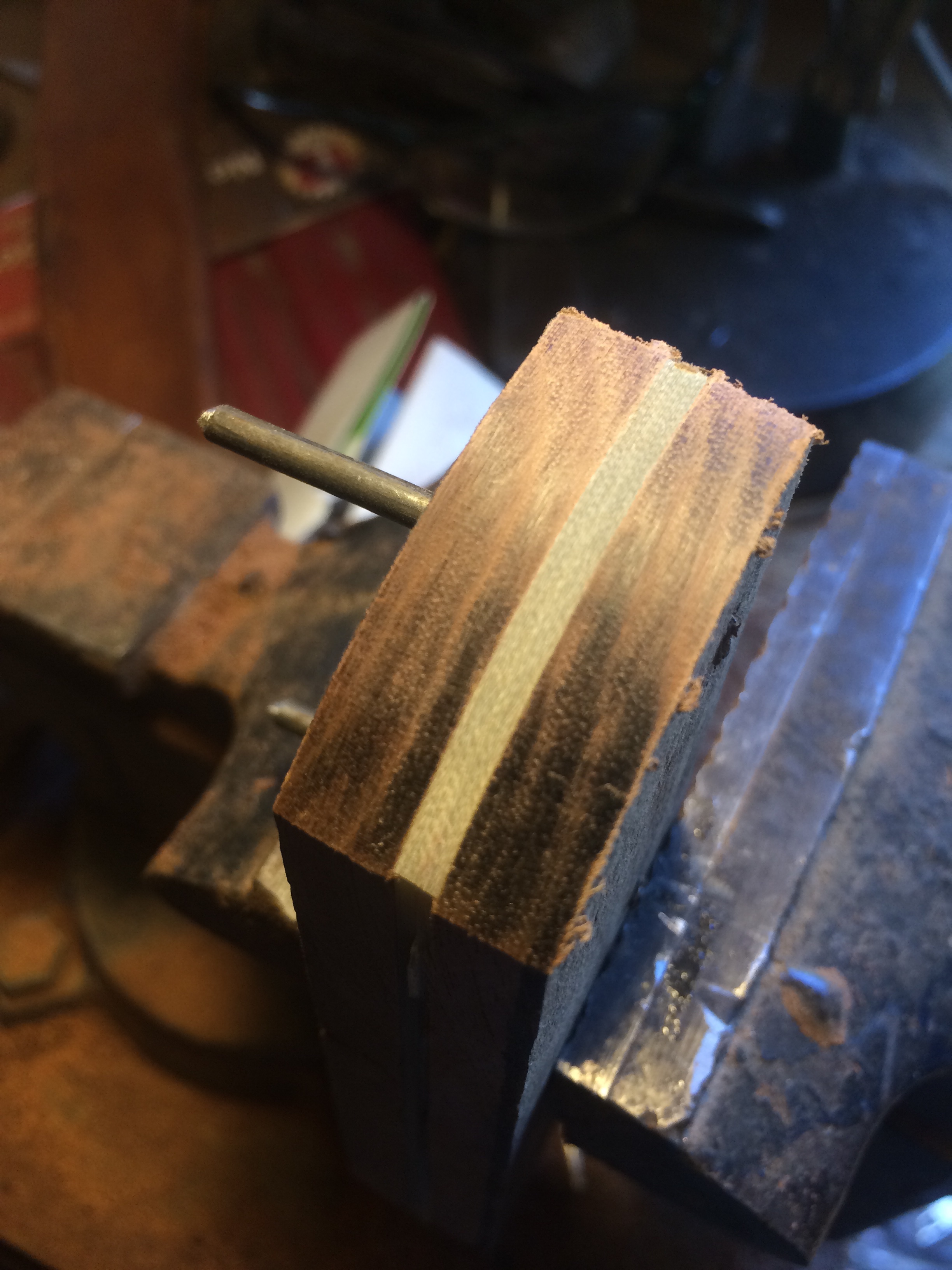

A leaf from a dining room table. It was pulled out of a lawyers house during an estate sale. I believe it is walnut or cherry.

The pants will make the bolster part of the handle.

The lawyer’s table will be the butt of the handle. We want the grain to be parallel with the length of the knife.

Everything will fit better if the rivet holes are drilled before it is cut in half. Because of the way this is made, the wood will be bookmatched.

PCB board blank. These were scrapped at work a few years ago. It actually has two sheets of copper just underneath each side. I’m not sure if they were supposed to let me take them but nobody has missed them.

That little flash of copper will be a subtle pop.

Countersinking the rivet holes will give a little play when fitting the handle. There are no precision tools in the shop and this will help negate any incongruencies I may make when trying to get this all together.

We need to polish this before fit up since we won’t be able to get at it once everything is fit up. 120 grit.

2000 grit.

All the pieces parts.

All glued and clamped.

Time to take away the parts that can’t be held

Profiled.

Flushed up.

Contoured.

He’d have been fired long ago if he weren’t so cute.

This is what it looks like at 220vgrit. We will take it up to 2000 and then buff.

All said and done we will probably do five coats of this stuff

Adding our mark.

The alligator clips are attached to a 6V battery. The nail polish acts as a resistor and current is only run to the area I marked. Connecting the circuit with the positive end through our conductor (salted vinegar) will burn our mark onto the steel. You have to use iodized salt- that delicious pink Himalayan sea salt won’t work.

The namesake of the knife gets etched onto the other side.

The Bob.