“I was a victim of a series of

accidents, as are we all.”

Malachi Constant, from Kurt Vonnegut’s The Sirens of Titan

A few years ago I went to see a therapist. I was stagnating. I had lost my job and was doing all sorts of ridiculous things to make ends meet. Over the course of about six months I floundered about. I worked security for outdoor festivals, fixed toilets in a friend’s apartment buildings, and did tree work with another friend.

I remember being baffled by the whole situation, and feeling like a victim of unfortunate circumstance. This wasn’t how any of this was supposed to happen.

Knives were not doing well. As I was sitting there staring at my belly button and not doing anything about my situation, it was suggested by those close to me that I go talk to someone who could help me. That was the last thing I wanted to do.

After some consideration, and a good amount of trepidation, I called a counseling office recommended by my insurance company and I went in for an appointment.

I remember sitting in a very Spartan office, with lamps suggesting a mood of emotional intimacy, and an institutional nightstand with a box of off-brand tissues sitting on top of it. My therapist walked in. He was a large African-American gentleman, crisply dressed, and carrying a folder.

He asked me the formal therapist/patient questions: what I hoped to accomplish in our sessions, and what it was I hoped to gain from our time together. The truth was that I was a little stuck. There were things about myself that I missed, a spontaneity and ease of being that I had lost. I knew where I was and I knew where I wanted to be but I didn’t know how to get there. Also there was a lot of emotional clutter and traumatic bullshit in the way. I told him all of this.

‘I think I can help you with that’, he said. ‘As for the emotional clutter and everything else in the way- I think it’s time to let that shit go’.

So we began. Nearly every two weeks for about a year, and then maybe once a month for the year after that. My therapist was technically a licensed clinical social worker who specialized in substance abuse counseling. I didn’t have any substance abuse issues- I had simply told the administrative lady at the office that I was most comfortable talking to a middle-aged man, and this gentleman had an opening. He didn’t wear a suit like all the other therapists. His dealings with addicts, I found, left him with a particular knack for getting to the root of personal problems , and a no-bullshit way of going about it, like a sort of Krav Maga of psychotherapy. I come from a place where you didn’t talk about how you felt so to voluntarily talk about things that were bothering me was, and is, something that is incredibly uncomfortable. And honestly I wasn’t looking to talk about what was bothering me- I was looking for someone to tell me what to do.

Of course that isn’t how therapy works. He didn’t tell me what to do. He would ask how situations made me feel and then challenge me. I came in one time really bothered about something and I remember him laughing at me. ‘Welp, you’re in the shit now’ he said, ‘What do you intend to do about it?’

The bluntness was empowering and it didn’t come with any judgement. This was simply how one large man was helping another large man. I would go in and tell him that my shit was all fucked up that week. And he would nonchalantly ask me if I had a plan for unfucking my shit, and that if I did not, perhaps there were some goddamn unresolved childhood issues being played out and my fucked up shit was just a manifestation of that. Then we would unpack my goddamn issues so that I could start unfucking my shit.

I would tell him that I struggled with faith that everything would be ok. He said everybody does. I told him I had a hard time dealing with disappointment and uncomfortable feelings that came from harboring resentments. I let him know I was ashamed about not being able to accept failure. He told me that all these made me a completely normal human being. Month after month he would talk me off of existential cliffs. ‘Don’t be a victim’, he would say. ‘Be a warrior.’

We talked a lot about transformation and how it can be difficult to change. I would be frustrated about something that was so deeply innate to my being that I didn’t know where to start. He would gently tell me that a person can only change so much, and some things simply can’t be changed. And then he would say that some of the things I was trying to change weren’t bad things and I should reframe what it was I was trying to do. It was a study in Buddhism, but with the boring parts left out, and a whole lot more expletives. When a sculptor wants to make a statue of an elephant from a block of stone, he simply removes the parts that don’t look like an elephant. There comes a point when you can’t remove anything else to make the stone look more like an elephant. This was what we were doing- removing (or at least identifying) the parts that didn’t serve the whole, and accepting everything else with kindness and compassion. Om Mani Padme Hum…

We laughed a lot. Lots of sad things came up, and I would get really weepy and reach for the off-brand box of tissues in that intimately lit office. We talked about music and books and art, and what it was to be a good man and what doing the right thing looked like. We usually ran over our time limit.

After a while I started bringing in the knives I was making and talking through the stories. It was like sculpting an elephant, or yourself, but I was taking away the parts that didn’t look like a knife. I was afraid it might be weird bringing big knives into a shrink’s office week after week but he told me to keep bringing them and to keep telling him their stories. So I did. I told him they were guardians that helped me to write the ridiculous experience that life has been for me. I’ve never done things the conventional way, or even the smart way, and bringing your handmade knives in to help you talk about your story with your large African American psychotherapist probably falls into at least one of those categories. He was always kind to that part of me. He told me to keep building little sharp guardians and to keep writing. At the end of each session I would shake his hand and thank him. ‘No, thank you,’ he would say. He said he always looked forward to seeing me on his schedule and to what I would come in and tell him. I think he dealt with people much more fucked up than I was.

I started seeing him less frequently. I found, slowly and when not crippled by self doubt, that I was getting to where I wanted to be and was able to find what I needed in myself. I was doing good things and feeling alright. He told me that much, and that nobody really knows what they are doing anyway, and he was always there if I needed him. He also told me to keep my knives sharp.

Every so often, when I’m about to do something dumb, I’ll hear that man’s voice telling me not to be a dumbass and I’ll think twice…

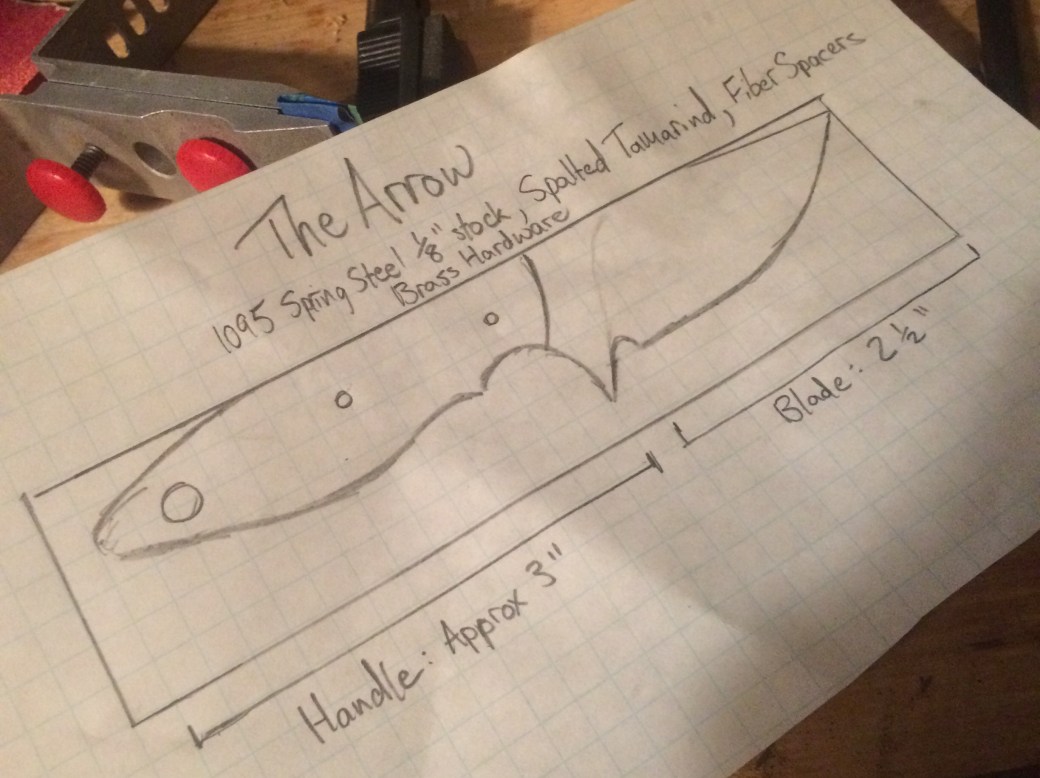

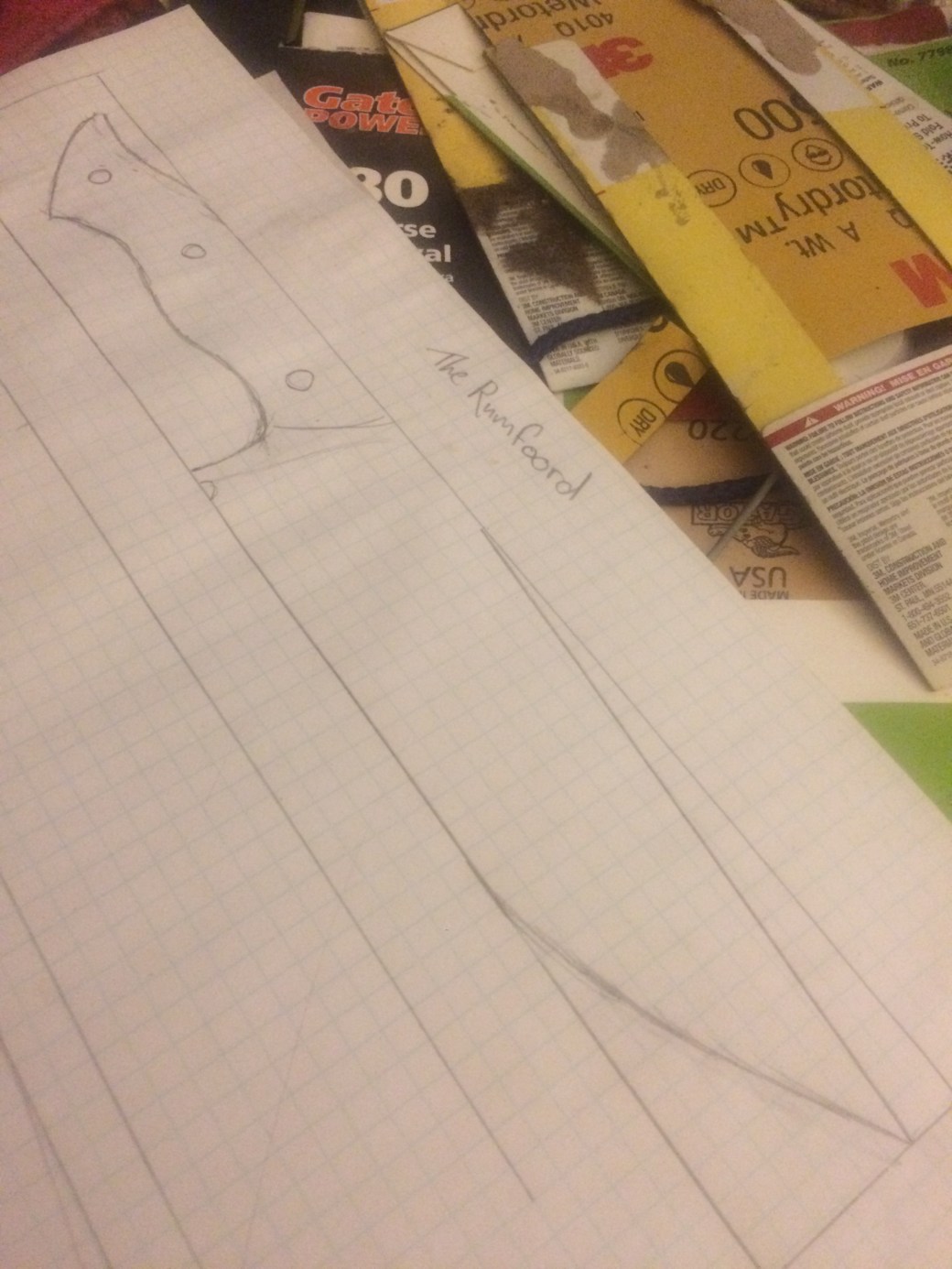

Sometimes one may know where they want to be but don’t always know how they’re going to get there. The journey to that destination is often the most interesting part of making it in the world. This blade gets it’s name from one of my favorite books, The Sirens of Titan, where the main character is at the mercy of the whims of chance and destiny (and also aliens), but through the grace of the almighty chonosynclastic infundibulum, ends up precisely at his foretold destiny. Along the way all of his core beliefs are challenged and his world is completely upended, yet there he is at the end of it all. This is the lesson of the Rumfoord.

This knife was built for a gentleman who was waiting a very long time for it:

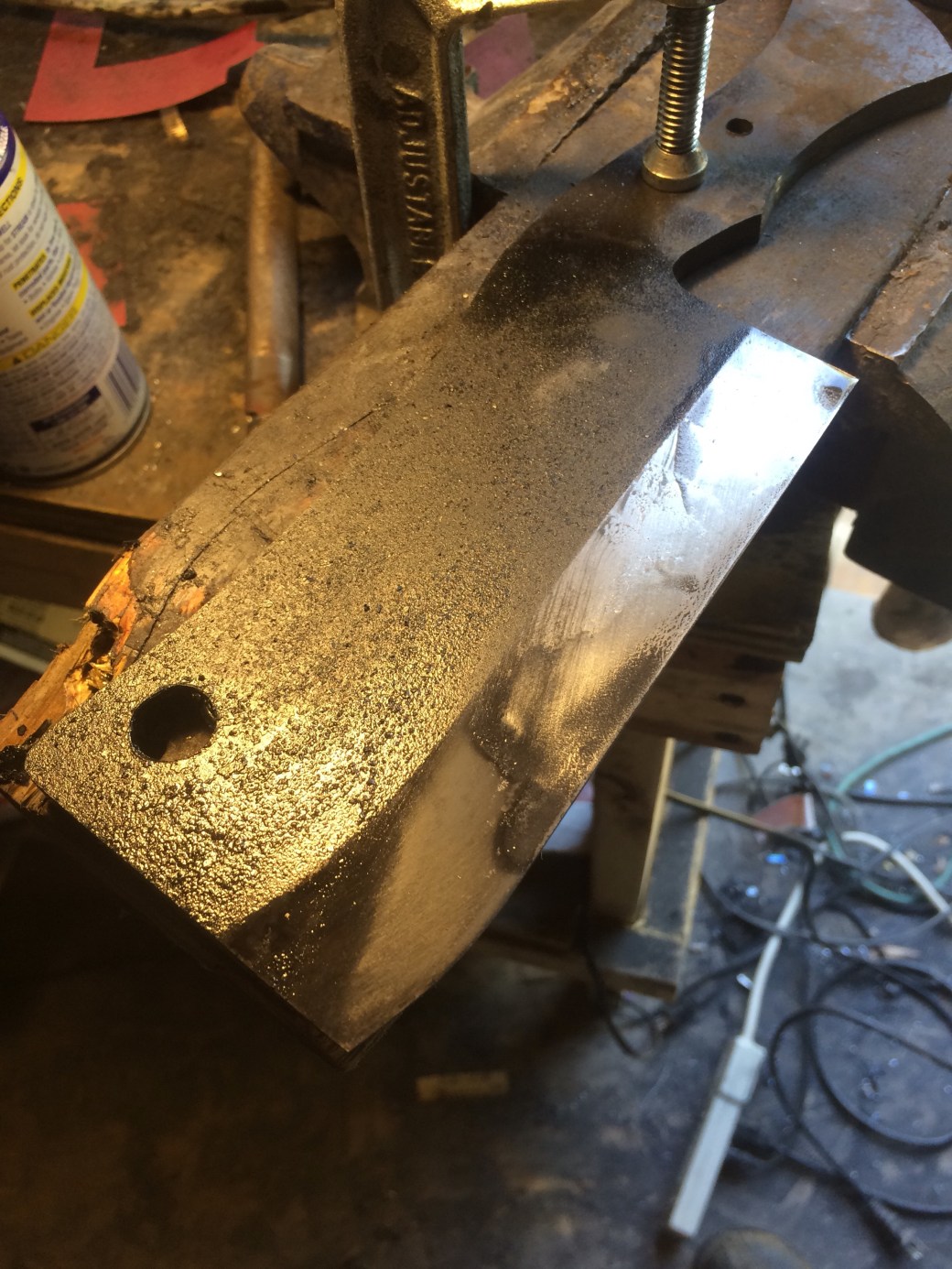

Heating can cause warping. A sophisticated setup for straightening…

Roughing in a full flat grind:

Removing all the machine marks…

…to achieve something a bit more pleasing. A smoother finish helps the blade to move through food better.

An acid etch to force a patina. This helps with corrosion resistance on the high carbon steel.

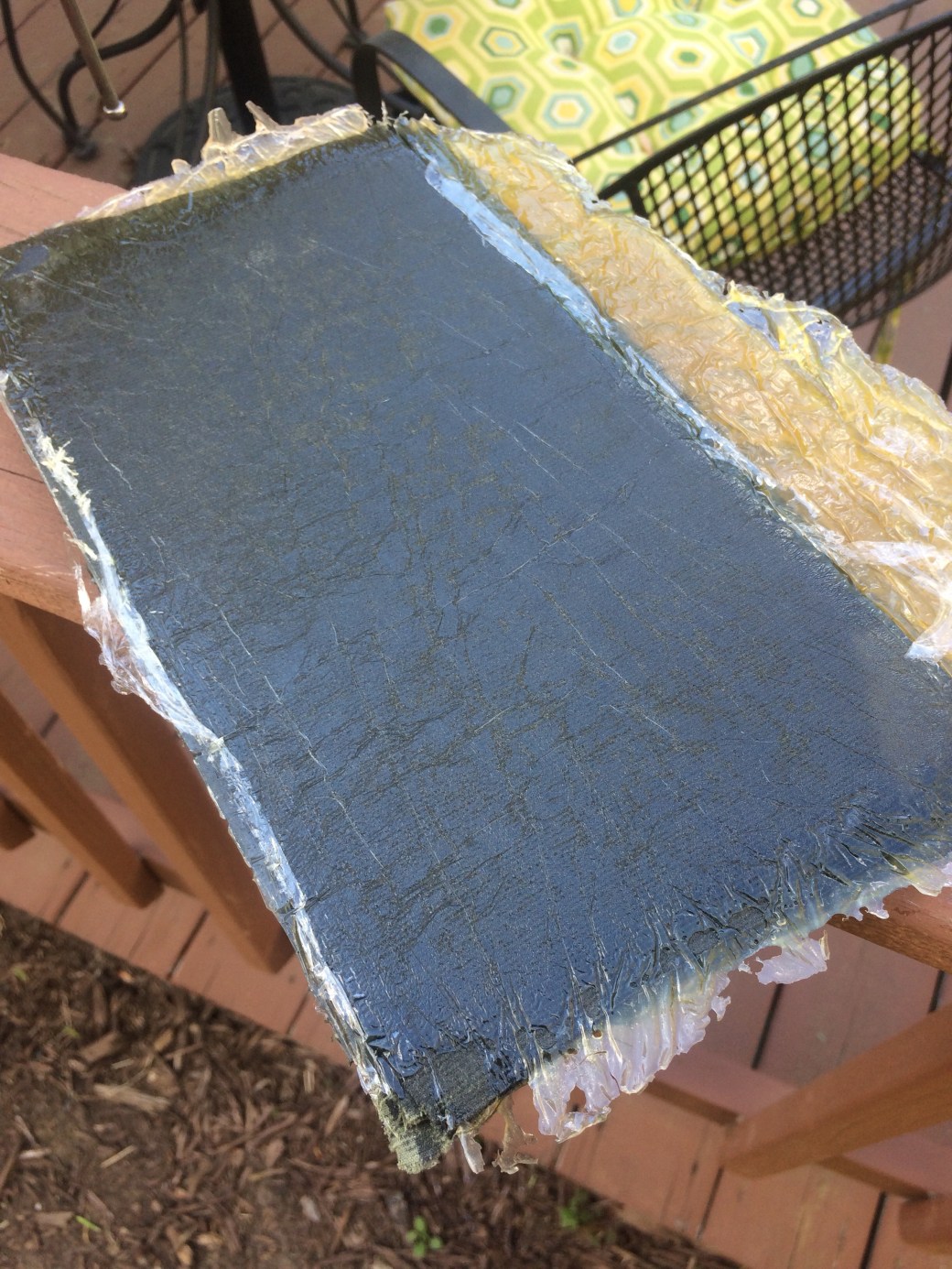

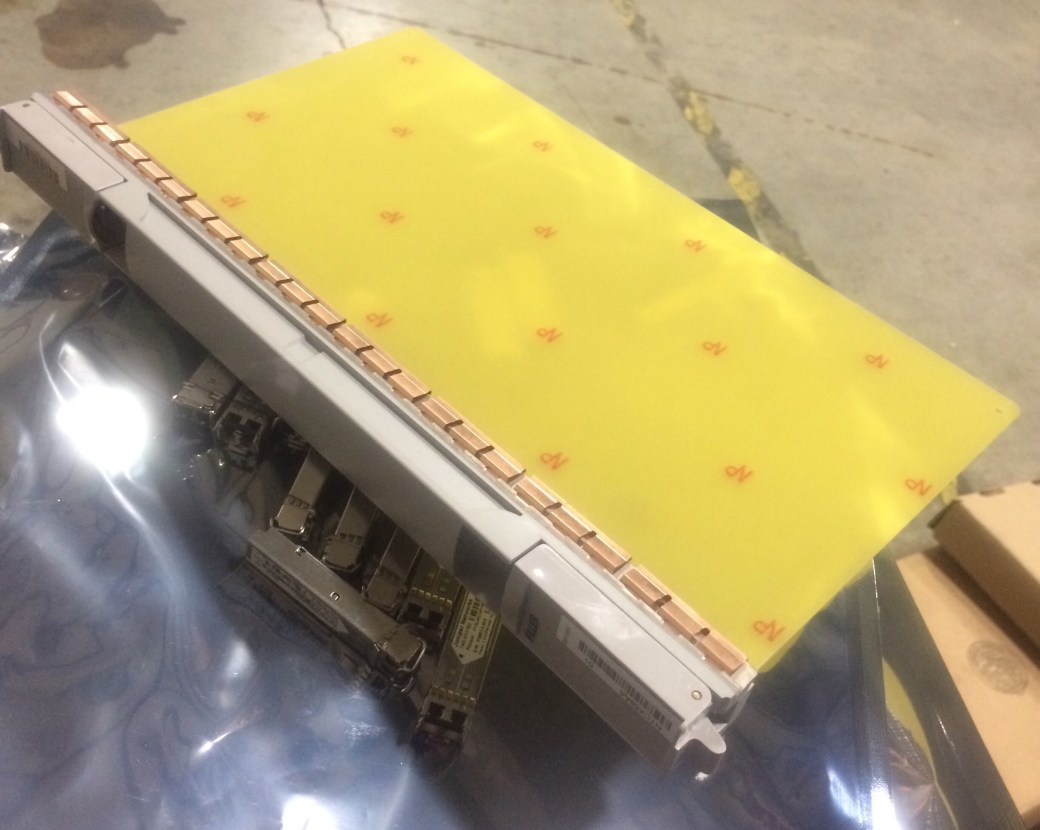

A PCB board blank from a server chassis. This will be spacing material for the handle:

Texas Pecan, from my cousin Bill:

Drilling out the rivet holes:

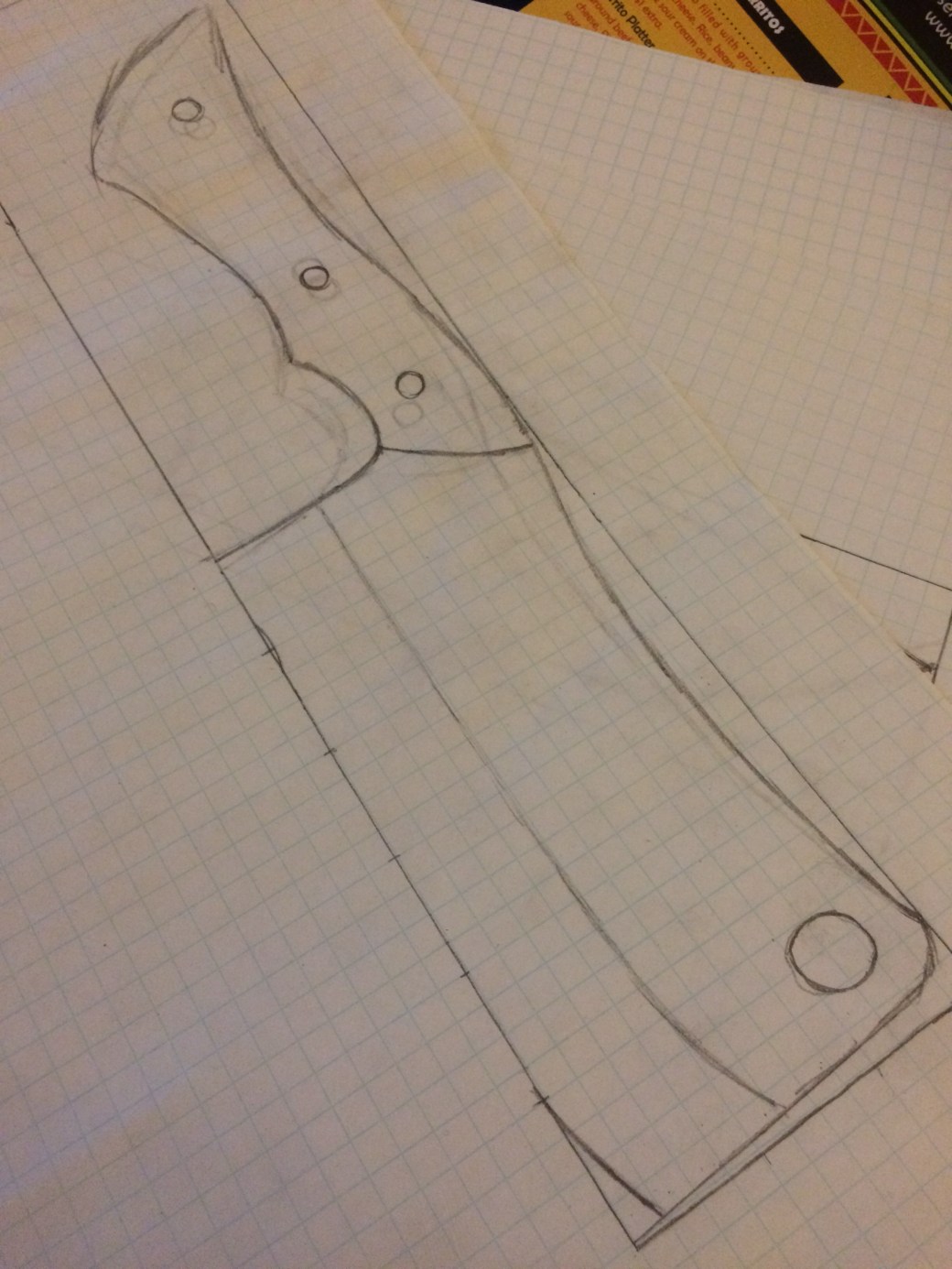

Laying out the handle profile:

The handle near the ricasso, at 40 grit:

The handle near the ricasso, at 1500 grit:

Glued up:

Profiled:

Shaped:

Smoothed:

The Rumfoord:

In a continued practice of saying ‘yes’ I chose to use some of the Black Walnut I got from the tree job for the handle material. It fit nicely into the story of these knives. This is what it looks like sanded and polished.

In a continued practice of saying ‘yes’ I chose to use some of the Black Walnut I got from the tree job for the handle material. It fit nicely into the story of these knives. This is what it looks like sanded and polished.