“The sword has to be more than a simple weapon; it has to be an answer to life’s questions.”

Miyamoto Musashi, The Book of Five Rings

(you can read about the crafting of the original Operator here)

I’ve always been drawn to people who do things. The people who speak through their work and translate knowledge and mastery through their particular skill set without having to say much. This is a day and age where anyone can broadcast claims of mastery and experience to a large audience and it can be difficult to discern who has done the work to back up these claims and who is just trying to get to the bank.

In today’s vernacular, ‘operator’ commonly refers to military personnel who are at the pointy-end of things. They are the ones who are taking the orders and quietly (or not so) doing the work out of a sense of duty and service. ‘Operator’ is a title that gets tossed around and claimed where it doesn’t always belong, very similar to ‘genius’. The ones who actually fit the bill generally eschew such titles. This is usually a symptom that you are doing the work.

This blade was a commission for a military serviceman doing Ops work. I wanted to build him a tool that would serve him in the work he was doing.

There was a summer about ten years ago where I was between semesters of study. I had decided that I wanted to learn how to fix things. Many of my friends were working at Blockbusters or car washes but I liked the idea of being able to take care of things myself. I took a really awful job doing apartment maintenance for three and a half months and did just that.

It was not very satisfying. The job I took was for a rental company who owned properties in my neighborhood so I could walk to work. It was a pretty slummish company that rented to a lot of college kids. I ended up having keys to half the apartments of what was called ‘Hell Block’ of a street close by to me. The summer was when a lot of leases ended so there were many people moving in and out. As a result the streets and alleys were full of discarded furniture for most of the summer, a lot of which was set ablaze by some of the rowdier tenants. Sometimes my days started with cleaning up the ashes of incinerated love seats.

Other days started with hauling four-burner stoves up three flights of a fire escape. Most of the time was spent flipping apartments from where someone had moved out so that someone else could move in. There was a lot of painting. Flat antique white for the walls and ceilings and semi-gloss eggshell white for the trim and kitchens. The apartments weren’t very nice to begin with and after three days of work they still didn’t look very nice. I tried to remind myself to just make it about the work.

I would spend hours gutting bathrooms- ripping out drywall, removing tiling, and replacing subflooring before redoing everything. The best days were when I could work by myself and keep my own company. Bathrooms were a bit more satisfying to do because they would actually look nice when you finished them.

There was one time when a new tenant couldn’t move into her apartment because a homeless person had moved in after we had flipped it. We went in the apartment after the police took him away and found no less than eight bicycles, some smelly furniture, and a plethora of bizarre pornography. There were also footprints all over the wall. We had to repaint that one.

My boss was a middle-aged anomaly with claims of ties to the trash hauling unions of New York City. I didn’t really believe anything he said. There were four of us handling most of the work orders:

-Mark was in art school, a bit cranky, and liked to smoke a lot of pot. Oftentimes it was hard to tell whether he was stoned or not. I liked him.

-Scott had gotten back from several tours of Iraq, most recently Abu Ghraib. He was a good guy but wouldn’t get anything done unless he was told exactly what to do.

-Mario was in his late thirties and from Guatemala. He worked 7 days a week and sent most of his money home to his family. He didn’t say much but I think he missed home. The man could eat faster than anyone I’d ever met. He said that in the Guatemalan Army they only gave you three minutes for lunch.

There was also a rotating cast of derelicts who would come in and work for a week and then disappear. I never learned their names.

One of the happiest days I had was telling my jackass boss that I quit. I gave myself a two week vacation before I went back to school.

What I learned at this job was that in order to get through many uncomfortable situations with a modicum of success you have to make it about the work. It helps to find something bigger than yourself in what you are doing. The skills I was learning would serve me well much later down the line, and the money would help me buy books and live through the school year and work on my education. Everything else was just bullshit that came with the job.

To let yourself speak through the work you do, whether you are toppling Marxist empires or replacing toilets in shitty tenements- this is the lesson of the Operator. In these situations our work speaks through us but also teaches us our lessons.

The recipient of this blade may find himself in harms way and needed a blade that would serve in such situations:

Rough cutting:

Bevels profiled:

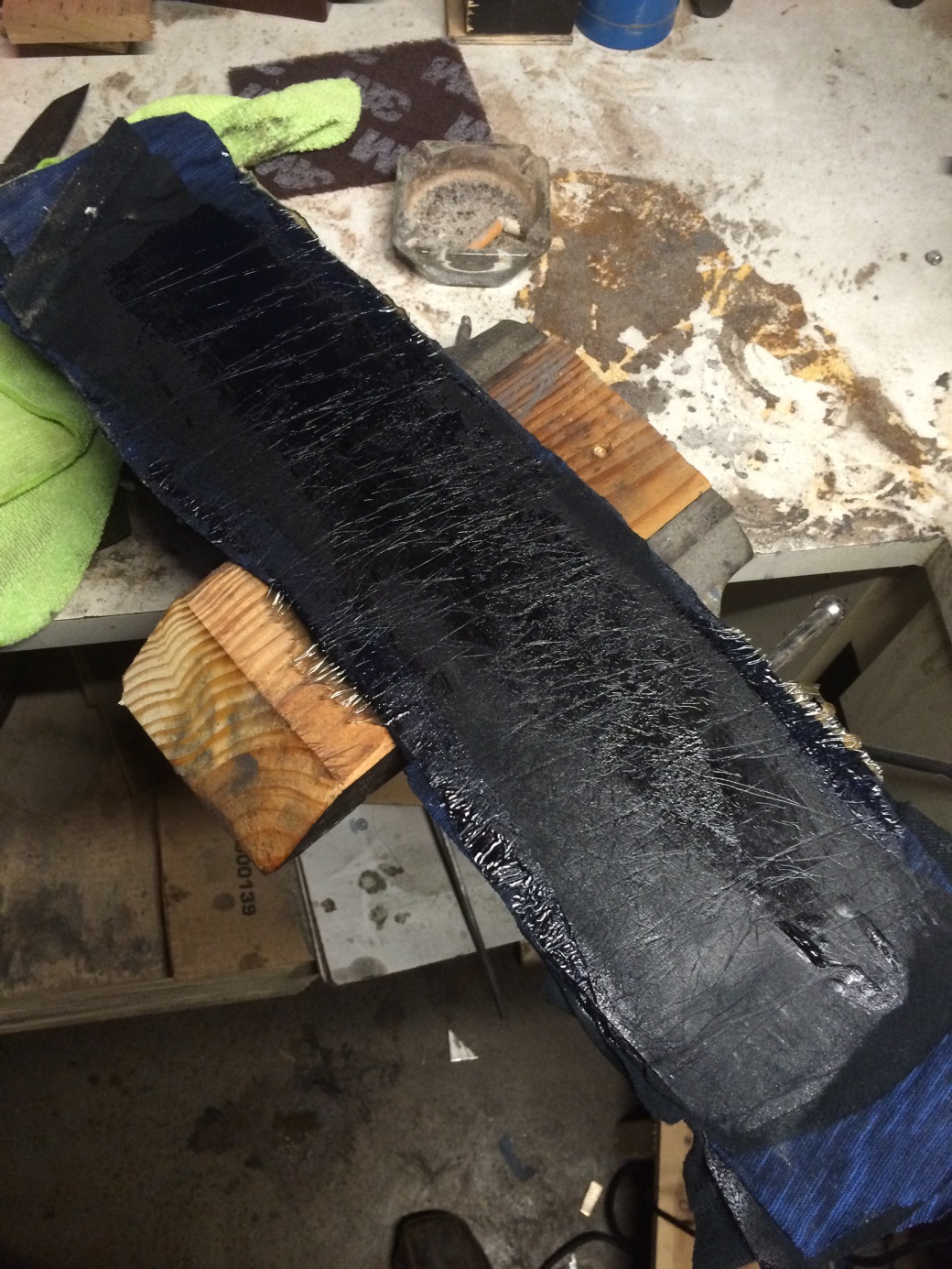

Hardened:

Hand sanding:

This is G10, a commercially manufactured synthetic material. Normally I prefer to make my own handle material but in this instance I opted for something consistently fabricated that would be failsafe in a potentially tactical situation:

The Operator, MkII: O1 tool steel, G10 scales, fabric spacers, and steel hardware.

Let your work be your lessons.