“i imagine that yes is the only living thing.”

― e.e. cummings

There are many things that come into our own personal worlds- children, possessions, problems, blessings and a myriad of others. It’s not so important how or why they enter our lives, but what we do with them. It expends a great amount of energy to ponder what we may have done to deserve the painful and traumatizing events that come to us, and an equal amount of energy is wasted when we wonder if we are worthy of the good things that are brought our way.

Because when we start dwelling on the why’s and how’s, we tend to become overwhelmed and lose sight of what best needs to be done with what comes into our lives.

And within that judgement of why and how, we start to say no to things. We become afraid we may be hurt, or that we may fail ourselves or those we care about. Perhaps we are afraid of making ourselves unsafe. Whatever the reason, in saying no we shut ourselves out of the blessing may be inside of a painful situation. We say no to what may be a path forward because it is dressed as something unpleasant. It is then that we become prisoners in our lives instead of seeing the ways we can be shaped and grow. We should say no to things that are harmful and do not better us, but it’s always good to say yes to what life brings us.

The summers are slow for me, and sometimes I have to get creative in the ways I support myself. I end up saying yes to many opportunities that under normal circumstances I would decline, usually due to time constraints, time away from loved ones, or a high probability of bodily endangerment (or a combination of all three). Over the years the things I’ve reluctantly said yes to have usually been the most rewarding.

One of the times I said yes this summer was to a tree job in rural Virginia. I was on a crew to cut down a huge dead tree. Removing dead trees can be dangerous. Rotting can occur in any number of unseen places of the tree, causing structural instability, and the tree may not fall where or when you desire it to fall. This particular tree, though dead as a doornail, fell exactly as it was supposed to.

The client was an artist, and brought us French-pressed coffee. We talked for a bit and I told him about making knives and how I got my materials. He told me that he had some slabs of black walnut and that I was welcome to them. They had been milled by a neighboring man who had run an abbey in South Korea, saying ‘yes’ to whatever fleeing defectors and dissidents from the North that the world brought their way. Later he sent me an article about the man who cut the wood, you can find it here. Black Walnut is expensive and isn’t something to normally fall into one’s path, so, in the practice of saying yes, I happily took some.

A week or so later I said yes to doing a bit of work on a good friend’s farm. My friend is a busy lady and sometimes needs a hand with the upkeep of her property. She and her family are good friends of mine. I worked for her son for several years and like to get out to their property as often as I can. It’s really beautiful:

She had a set of knives she wasn’t sure what to do with. They belonged to her late husband, and came to him from his grandfather, who was an Austrian immigrant. He came to the United States in the early 1900’s and made his living as a chef, choosing to say yes to a new world and a new life. She told me she’d like to have them restored so they can go to her children and stepchildren to remember their father. I told her I would have a look at them and see what I could do.

Tools of the trade, from left to right: A carving knife; a fish knife; a French slicing knife; and a 12″ chef’s knife

So these knives came to me, at least a hundred years old, and of deep sentimental value. I started by removing the cracked and broken handles.

I cleaned up the corrosion and oxidization from the blades, but left much of the etched patina from their years in the kitchen.

In a continued practice of saying ‘yes’ I chose to use some of the Black Walnut I got from the tree job for the handle material. It fit nicely into the story of these knives. This is what it looks like sanded and polished.

In a continued practice of saying ‘yes’ I chose to use some of the Black Walnut I got from the tree job for the handle material. It fit nicely into the story of these knives. This is what it looks like sanded and polished.

All of the handles started as thin blocks cut from the Black Walnut.

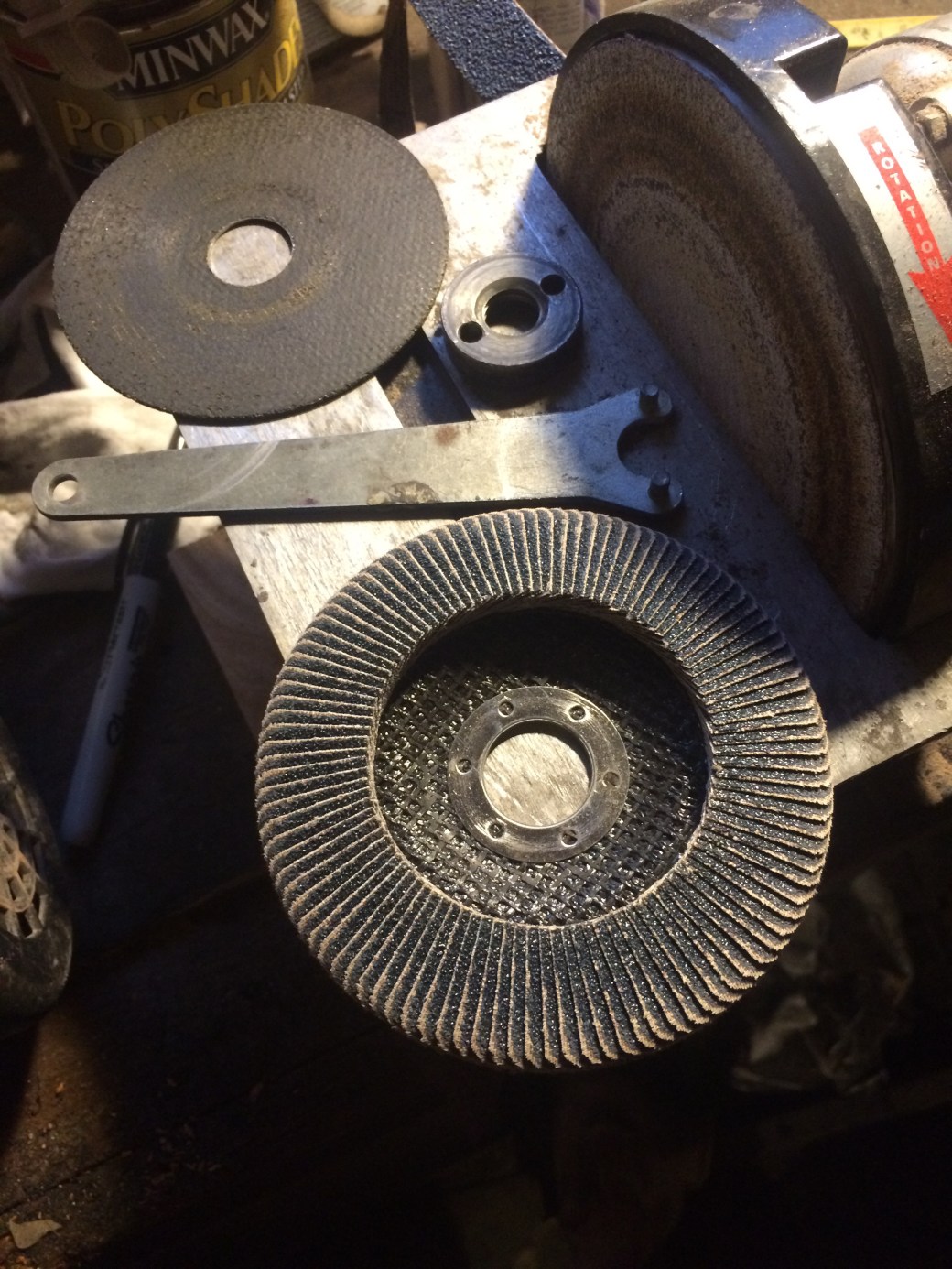

Shaping.

The filet knife was only half-tang, so I extended it with mild steel from a sheet.

I added a G10 bolster and spacer for a bit of contrast.

After glueing and sanding.

Getting the fish knife ready for glueing and shaping.

The French slicer was tricky….

…but also an elegant challenge, with its tapered tang and integral bolsters.

Finished, they came out rather beautifully:

Say yes to the things that come to you whenever possible. It’s always worth it on the other side.